(S1E1) Against The Tide: The Bellevue Passage Museum

“What does it take to preserve a community on the verge of disappearing?”

You know, the thing about Bellevue was - it was all black. So I never really... I never felt racism. That sounds dumb, it? I never dealt with can't go in here and have to look down, couldn't look at people, or couldn't speak to certain people. I never dealt with that. It was not something that we experienced in Bellevue. Because everything looked like me. You know what I mean? Everybody looked like me. Everybody looked like me.

—Carrol Wilson, Former Bellevue Resident

Bellevue Historical Overview

Bellevue Packing House, Chesapeake Bay Martime Museum

Bellevue Village, one of twenty-two incorporated villages in Talbot County on Maryland’s Eastern Shore, is one square mile, consisting of roughly seventy dwellings and eighty residents, and is one of the few remaining historically Black maritime and working-class communities in the region. Settled in the aftermath of the Civil War, Bellevue was notable for its self-sufficiency.

For generations, Bellevue was a place of belonging. All Bellevue businesses were black-owned except for the Valliant Packing House, Cannery, and General Store. Vegetable gardens and livestock were common, and the community hosted several companies and cultural and social sites and activities, including a Rosenwald School, Knights of Pythias Lodge St. Luke’s United Methodist Church, general store, post office, four restaurants, recreation center, gas station, doctor’s office, baseball league, and Boy Scout troop. Most notably, the W. A. Turner & Sons Packing Co. (1945–1996) and Bellevue Seafood Co. (1964–1998) were one of the only two African-American–owned seafood processors on the Eastern Shore, employing over seventy local watermen and women and anchoring the village’s economy from World War II into the early 1990s.

The Death of An African American Community in Talbot

Yet Bellevue’s success sowed the seeds of its decline. Few returned to the packing houses as the children of watermen and women pursued college and professional careers, realizing their parents' hopes of a college education for their children.

In other ways, Bellevue succumbed to outside forces. By the 1980s, oyster and clam populations had collapsed, decimated by overfishing, pollution, disease, climate change, and storms such as Hurricane Agnes (1972), forcing both companies to close. Geographically isolated and without industry or basic infrastructure (roads, sewers), Bellevue struggled to attract newcomers. Its population dwindled, and its character shifted under the twin pressures of neglect and gentrification.

As houses became unoccupied, retaining familial ownership became increasingly challenging and financially infeasible for inheritors in Bellevue and elsewhere. Talbot County’s booming waterfront development and rising property taxes drove longtime families to the margins.

Once 27 percent Black in the mid-20th century, Talbot now counts just 11 percent—and boasts Maryland’s most significant wealth gap, with the top 1% earning nearly 35 times the average income of the bottom 99%. In the present, Bellevue’s storied buildings and landmarks have vanished mainly as long-term residents navigate a changing landscape.

It Takes a Village: Resisting Gentrification; Building a Museum

“I found that meeting absolutely disgusting. It was a wasted effort. They came presenting a plan where we had no options whatsoever. It was already settled. Nothing we said was going to change what was going to happen, and that really ticked me off. It really did. If they really wanted our input, they would have started from the beginning. And they didn’t. It just wasn’t done right. It wasn’t done right.”

Bellevue Passage Museum

Museum Co-Founder Dr. Dennis De Shields, on the motivating factors to develop the museum.

Dr. Dennis De Shields never set out to build a museum. “Well, actually-this is just something I kind of landed in-if you’d asked me three years ago, I’d have said, ‘Are you out of your mind? I’m not doing that,’” he laughs. Then developers began carving Bellevue’s shoreline into multimillion-dollar home sites—plans for fourteen luxury properties that threatened to displace residents, negatively impact the local environment, and threaten erasure of the village’s history and culture. In April 2022, residents packed St. Luke’s Methodist Church to voice their objections, only to face a brick wall of pre-approved permits and polished renderings. Although the community’s objections fell largely on deaf ears, the outcry galvanized it to reclaim agency over its future. Today, the Bellevue Passage Museum stands as both a bulwark and a beacon. A grassroots testament of love, urgency, and collective conviction to preserve a way of life on the verge of disappearing. “And so it was put on my heart at that time that we [Dr. Dennis and Dr. Mary De Shields] were in a position where we had resources that would help us create a museum,” Dennis explains.

Repurposing a Historic Property

The museum’s future home, “Pick’s Place,” is a humble 15×20-foot former restaurant. The refurbishing process will add an adjoining annex to house artifacts and oral histories generously donated by residents and descendants.

Navigating Bureaucracy with Community Behind You

Museum Program Director Kat De Shields-Moon on the need to chase Black history and legacy.

Securing zoning and planning approvals in Talbot County tested the Bellevue Passage team’s resolve. At council hearings, Dennis De Shields was accompanied by legal counsel, architects, and a contingent of Bellevue residents and supporters. Though only two formal complaints surfaced at a critical Special Exceptions meeting on September 9th, 2024, the pressure felt “like the end of the world,” he admits. “Having the lawyer talk me off the ledge—and even planning and zoning staff saying, ‘This isn’t a big deal; here’s how to address those concerns’—gave me the confidence to keep pushing.” For two intense years, he found himself before one committee after another, each time “telling the same story, and I felt like I was wearing out my welcome.” When the final vote passed unanimously, Dennis turned to discover supporters filling every pew—even some he hadn’t noticed arrive—and felt a wave of communal triumph. “This is something others may have thought of—this museum—but didn’t have the resources to do that. Now we can certainly come and say, ‘Yes—this is going to happen,’” he reflects.

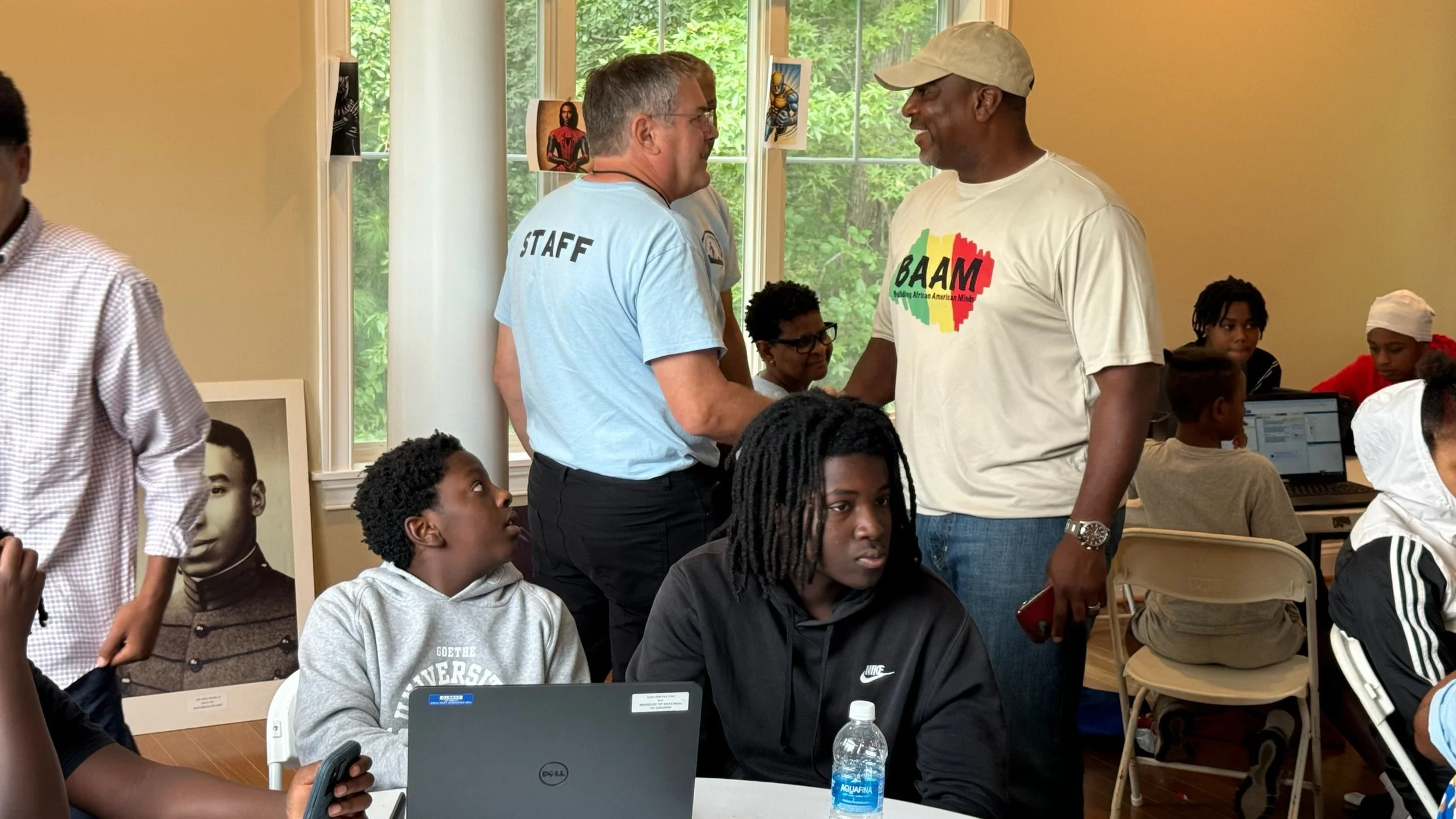

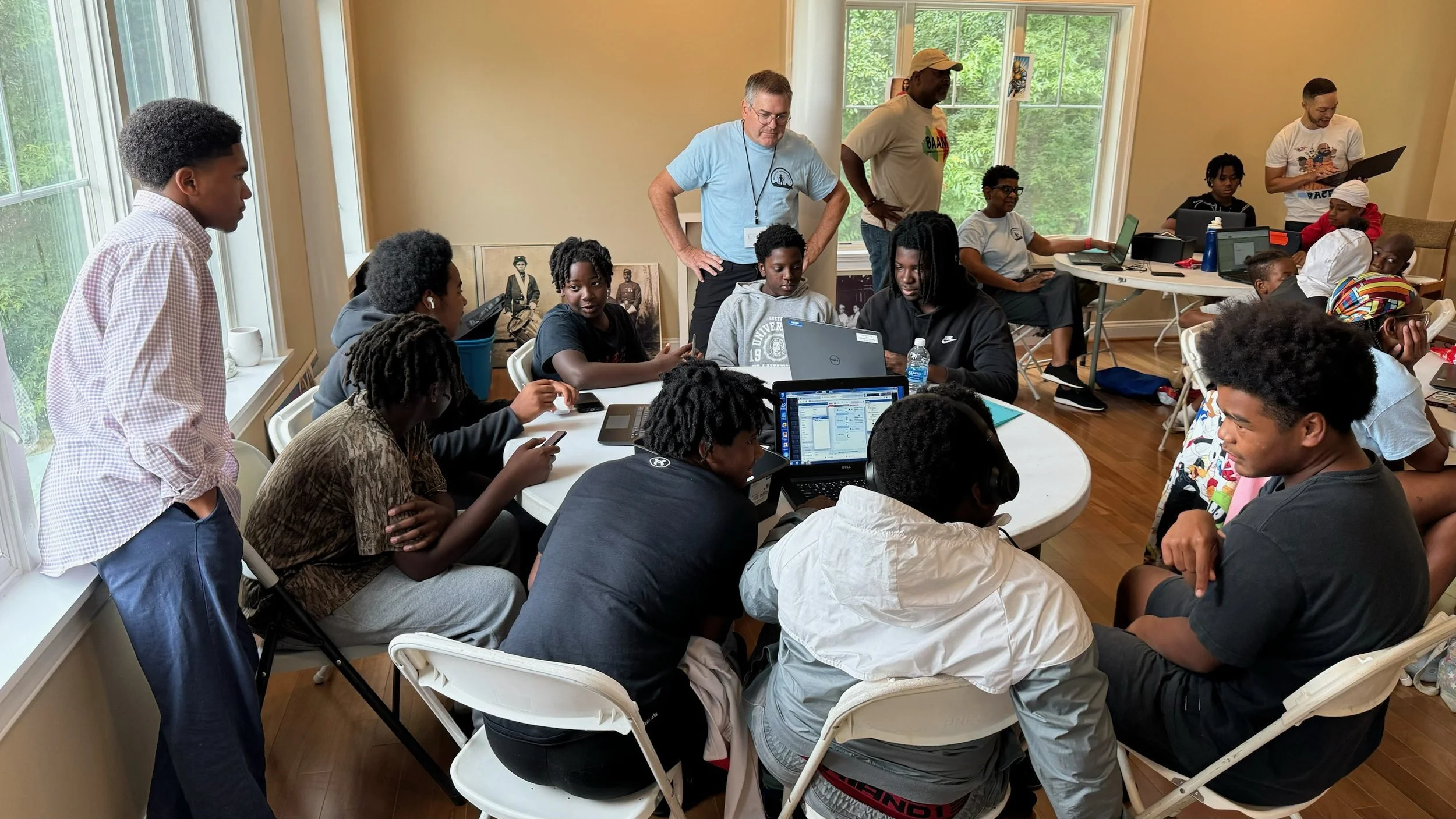

Tackling “Jim Code”: The 2024 STEAM Summer Camp

The De Shields family and the Bellevue community see the museum not just as a window into the past but as critical to envisioning the future. Through the museum, they consider programs mentoring high-schoolers through post-graduation choices, planning a kitchen garden to reintroduce self-reliance and traditional practices into the community, and harnessing digital tools so that no local finds themselves left behind by “Jim Code”—the modern tech gap that echoes historic Jim Crow barriers, a concept explored by Ruha Benjamin in Race After Technology: Abolitionist Tools for the New Jim Code. “I've been in the gaming industry for about 10 years, and unfortunately, when I first got in,” Kat notes, “the sum total of black people in the gaming industry was 3 %, and 10 years later, we're at a whopping four. My focus is making sure that nobody misses the bus when it comes to all of the wonderful things that are available in the technology space.”

For Kat, her return to Bellevue in adulthood sprang from the stillness imposed by COVID-19. When the pandemic grounded her normally social life—it forced a reset that revealed what really matters. That enforced pause cleared the way for Bellevue, a place she might otherwise have bypassed for Atlanta or Pittsburgh. Discovering she and her husband were expecting their daughter brought a single thought to mind: Bellevue’s deep-rooted sense of community. It called her home. What began as occasional help at the Bellevue Passage Museum—“dab here, dab there”—quickly turned into a full-hearted, long-term commitment.

Last summer’s pilot STEAM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Arts, and Mathematics) camp showed how richly the mission to ensure opportunities for Black children in technology could unfold, in a programmatic vision fueled by Kat’s technology expertise. Over five days, local children experimented with molecular chemistry, merged superheroes into art-history mashups, and learned basic coding alongside volunteer mentors. “It was tapas-style learning: break a bunch of ideas on the wall, see what sticks,” Kat laughs. “We had four community volunteers, plus Building African American Minds (BAAM) students,” Kat smiles. “It was amazing to see which projects resonated: some kids loved the chemistry demos, others were all about remixing art.”

In an age of relentless development and rapid change, the Bellevue Passage Museum offers a preservation model rooted equally in people, history, and place. “To make it sustainable for me is to invest in people's lives,” Dennis reflects. “To try to help people to live the best life that they can live with the potential that's in each of them.”

Follow and Support the Bellevue Passage Museum

Website: https://bellevuepassagemuseum.org/

Email: info@bellevuepassagemuseum.org

IG: https://www.instagram.com/bellevue_passage/