(S1E5) On Sacred Ground: The Gullah/Geechee Cultural Community Trust

What does it mean to sustain a living culture and a community still fighting for recognition, where even the burial grounds are contested, and challenging development means standing for both the dead and the living?

Awakenings: Founding the Gullah/Geechee Community Cultural Trust

Glenda Simmons-Jenkins

Co-Founder and Executive Director, GGCCT

Sometimes, we don’t fully recognize the truth of who we are until something—or someone—opens the door. For Glenda Simmons-Jenkins, Founder and Executive Director of the Gullah/Geechee Cultural Community Trust (GGCCT), that moment came on a Sunday afternoon visit to American Beach, a historically Black beach community on Florida’s northeast coast. She had come to visit MaVynee Betsch, famously known as “the Beach Lady,” whose fierce activism helped preserve American Beach from the forces of development and erasure. It was in Betsch’s home that Glenda was introduced to Queen Quet, the Chieftess of the Gullah/Geechee Nation.

That meeting changed everything.

“She introduced us and from that moment until this I have been championing the importance of Gullah/Geechee culture and heritage for our community, for this region,” Glenda said. “But it started with my family. It started with this enlightened moment in which I was like—You mean all along this is who I was and I didn't know it?”

That realization rippled outward to her family, to her community, and ultimately, to the creation of a movement rooted in cultural memory, ancestral protection, and land preservation. As Glenda shared her discovery, her loved ones experienced their awakenings. “Having them to also have that light bulb moment where this all makes sense,” she recalled, gave her work new depth and urgency.

Soon after, Glenda was elected in 2004 to serve as a representative on the Assembly of Representatives for the Gullah/Geechee Nation during the official ceremonies on Sullivan’s Island. From there, she helped establish the Gullah/Geechee Cultural Heritage Committee of Northeast Florida, the first grassroots Gullah/Geechee advocacy initiative in the region.

Still, something more permanent was needed—something that could take on the escalating threats to sacred land and Black heritage in northeast Florida. That need came into sharp focus in 2020.

“One of our elders on the council of Elders informed me of burial grounds potentially being disturbed in Yulee for the clearance of trees for a shopping plaza,” Glenda explained. “And doing that work to help stop the development long enough for us to be able to determine whether burials were there… is sort of what launched GGCCT.”

As they fought to protect the site, it became clear that a formal organization was essential. “It was in my heart for a while that we needed an organization that would do the advocacy work,” she said. “But what spurred it was the fact that we realized… we really needed to formalize and we needed a support system and we needed to be a 501(c)(3). And so that's how the organization came to be.”

Kathie Carswell

Operations Director, GGCCT

That organization became the Gullah/Geechee Cultural Community Trust (GGCCT)—a nonprofit rooted in the defense of ancestral burial grounds, historic Black communities, and cultural continuity.

For Kathie Carswell, the Trust’s Operations Officer, this wasn’t just preservation work—it was a family inheritance. “It’s passed on from my mother and her mother,” she said. “My mother was the historian for our family.” Her mother had grown up on land that developers now eyed for profit, so from early on, Kathie watched her fight to protect churches, cemeteries, and oral histories that had defined their lineage.

After her mother passed, Kathie stepped into her shoes. She joined the Franklintown Cemetery Association, took on stewardship of their family’s church, and began speaking publicly about their history. “And also, by us being placed right here on American Beach with our church and my family home being further down Louis Street, it was a no-brainer for me to… be the spokesperson for our family's history and to make sure it continues to move forward.”

That’s where they are now: leading GGCCT not as career preservationists, but as daughters, descendants, and defenders of a people, a land, and a culture that refuses to be forgotten.

“They Didn’t Abandon It”: Sacred Sites, Displacement, and the Long Memory of the Land

Rudolph Henderson and Kathie Carswell walk through Crandall Cemetery, the site where members of Henderson’s family are buried on corporately owned forestry land. Courtesy of the GGCCT.

Before the Gullah/Geechee Cultural Community Trust had a name, before it was a 501(c)(3), before any organizational paperwork had been filed, there was a burial ground. And then another.

Glenda Simmons-Jenkins remembered it clearly. “When we became aware of the first… the Trust hadn’t organized yet,” she said. “We were just kind of on the cusp of knowing something needed to happen. And then that happened in 2020, that we found out about another burial ground. And the second burial ground… is what triggered the organization to organize, to be established.”

Since then, the Trust has taken on the painstaking work of identifying and protecting Black cemeteries, especially those on private property or in rural areas where memory often outpaces documentation. The work is slow, frequently reliant on oral testimony, handwritten records, or moments of serendipitous discovery.

“In the last month, I came across death records for another area that I didn’t know had burials,” Glenda said. “But clearly, Black people are buried there, because it says the place on the death record. No one’s talking about it.”

GCCTT accompanied descendants on a visit to another Gullah/Geechee burial ground located on corporate forestry land in Yulee, FL. Courtesy of the GGCCT.

The silence surrounding these burial grounds isn’t always willful—it’s structural. It's what happens when displacement severs people from the places their loved ones rest.

One cemetery the Trust is actively protecting is Crandall Cemetery, for which they received funding through the state’s Abandoned African American Cemeteries Grant Program. But even the language used in that title—abandoned—gives Glenda pause.

Vietnam Veteran Eugene Hunt pays respect to his grandfather, WWI Veteran James Hill Jr., who is buried at Crandall Cemetery. Courtesy of the GGCCT.

“That word abandoned is something that I challenge when I speak about it,” she said. “Because in most cases, when you hear the word abandoned, the connotation is: they left it behind, forgot about it, didn’t care.”

But that’s not what happened. Not in these communities.

“When our community members get displaced, they have to leave behind—not the least of which is the cemetery,” Glenda explained. “And in their leaving it behind, it’s not that it’s forgotten. But your lack of proximity to it means that maybe you don’t talk about it. And when you don’t talk about it, your descendants don’t hear about it. And when they don’t hear about it, then it’s forgotten.”

It’s not neglect—it’s forced distance. And the Trust is working to close that gap.

One site they’re currently pursuing lies deep in the woods on private land. Only one elder in the community knows how to find it. “He gave us all of the directions, the instructions, how to get there,” Glenda said. “And it’s going to take us some time to be able to navigate it because there’s a process that you want to go through that doesn’t tip people off before you actually get a chance to secure it.”

He’s the last living memory of that place. “And he’s in his 80s,” Glenda added. “And we’ve pledged to him that we’ll do everything we can. It’s just taken us a little longer than we had hoped. But we have it documented, and we know where it is. And so it’s on our list.”

Presence in the soil. Presence in the story. And presence in the present. Because these cemeteries were never abandoned. They were interrupted.

And now, the work is to return—gently, intentionally, with names on their tongues and elders at their side—to places long left untended but never unloved.

Preservation, Sustainability, and the Right to Remain

Glenda was a child when it happened.

She remembers the moment vividly, even decades later. “I was like seven or eight years old when my parents got the knock at the door, offering them some... miniscule amount of money.” She paused. “And that experience just stays with you.”

GGCCT Founder and Executive Director, Glenda Simmons-Jenkins on her experience with displacement.

That early dislocation didn’t just mark her—it mobilized her.

“Having that experience is what allows me to have the drive and the energy around this public advocacy. So the role that I'm playing now is just a continuum of where it all started.”

There’s something both sobering and powerful in hearing her say it so plainly: “My family being uprooted not because we want to be, but because someone said we had to be. And so justice for me is at the core of my being because I experienced injustice so early.”

Her work with the GGCCT is about safeguarding a living culture. “Preservation is about what you’ve managed to hold on to,” she said. “But sustainability is different. It’s about still actively existing as a people—and making sure you don’t lose anything more.”

That difference matters. Especially when you’re fighting for land, legacy, and voice in a system designed to sideline you. Glenda and her colleague Kathie Carswell know that firsthand. “We both know what it’s like to have government authority say: this land is no longer yours. You have to go.”

Now, they’re up against both corporate developers and opaque local governments. “Often we don’t find out about a project until it’s already underway,” Glenda said. “And we’re expected to just accept it. But our ancestors are in the path of what they intend to do—and we will not be silent.”

It’s not just about protest—it’s about power. “We may not have high-powered lawyers or deep pockets,” she said. “But we have our voices, our bodies, our minds, our ancestry. We have God. We have everything we need to challenge the status quo.”

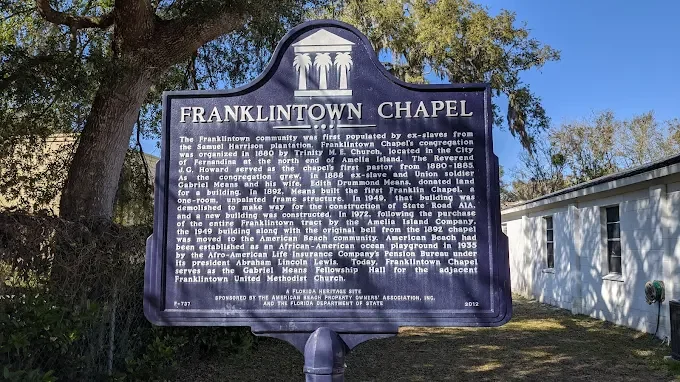

That principle is embodied in the story of the Franklintown Episcopal Methodist church. The church is a survivor. And its story, as told by Kathie Carswell, spans generations, migrations, and the fight to hold onto sacred land in the face of erasure.

Franklintown Chapel Historical Marker, installed 2012

The struggle to hold on to land is a shared one between Glenda and Kathie. “That's another common thread that runs through my relationship with Kathie,” Glenda said. “We both know what it's like to have government authority say, this place that's your home and your land can no longer be your home and your land. And you have to go somewhere else.”

In the early ’70s, Kathie’s family and neighbors were forced to sell their land for development. But they refused to leave everything behind. They put their church—rebuilt in 1949 after a state road tore through the community—on a flatbed truck and moved it across the island.

That vision, born of faith and self-governance, is what allows this space to still stand—137 years later. The land where it now stands holds generations of memory: Kathie’s family home, her grandmother’s, her great-aunt’s. They named the new gathering space, the Gabriel Means Fellowship Hall, after Kathie’s great-great-grandfather, who donated the original land for the church as a freedman after emancipation.

To Glenda, churches like Franklintown aren’t just places of worship—they’re cultural anchors. “They’re monuments to self-determination,” she said. “They’re one of the few places where you can walk in and feel: this is my place.”

It’s the same spirit that flows through all Gullah/Geechee lands—the rootedness, the dignity, the unspoken welcome. “That feeling is what you experience—or what you should experience—when you walk on Gullah/Geechee lands,” Glenda said. “And it's why we advocate for that so much not to be taken away from us.”

In a world that often treats Black land loss as a footnote and Gullah/Geechee culture as a curiosity, their leadership insists on something different. It insists on presence. On permanence. On the truth that preservation isn’t just about looking back, and sustainability isn’t just about survival. It’s about the right to remain, to speak, and to shape the future, not from the margins, but from the center of one’s own story.

Self Determination Starts Here: Community Voice, Land, and Legacy

At the core of the GGCCT’s mission is self-determination: the right to stand firm, speak clearly, and shape a future grounded in ancestral memory, not outside permission. But as Glenda emphasizes, that begins with reclaiming a voice in the very spaces where it’s been long ignored.

Some of the most challenging topics they’ve had to confront aren’t even new—just long buried, sometimes literally. “Local government,” Glenda said plainly, when asked which spaces they’ve had to push into. “And I will say it's not to say that our community has been inactive. It's that we are active in sometimes a reactive way. And sometimes that's not our fault.”

Often, the timeline isn’t built for transparency. Decisions are made before notice is sent out. Projects are halfway through before communities even learn they exist. “By the time we learn about it, the momentum is already there for it to move ahead. So we have to jump in where we can.”

Franklintown Community Church of Amelia Island

Right now, they’re confronting both corporate and governmental forces—often simultaneously. “We’ve got those two things that are working in tandem,” Glenda said, “where we have a corporate issue that we’re dealing with and we have a government issue, and those two things are sort of colliding around our ability to protect those burials that are on corporate property.”

To resist, they’ve had to move beyond conventional advocacy. “You step outside of the box and you say: this is what we are going to do. We are going to use the tools that are at our disposal. We may not have high power corporate lawyers. We may not have bank accounts full of the monies that we need. But we have our voice, we have our bodies, we have our minds, we have our ancestry, we have all of that at our backs. We have God. We have everything that we need to challenge the status quo.”

That clarity anchors the Trust’s motto: “We create solutions at the intersection of land and culture.” As Glenda puts it, “We cannot have culture without land. And we keep our land by exercising our right to self-determination.”

Familiar obstacles—funding, visibility, exclusion—are compounded by the Trust’s radical stance: defending Black land and memory in a region that often romanticizes Gullah/Geechee culture while erasing its people. Even their earliest hurdle had nothing to do with money.

“In the beginning, one of our challenges was to have legal advocacy that really understood what it was about and what we intend to accomplish,” Glenda said. “We did not come into this to play soft.”

Their work is disruptive by design. “We came into this to rub people the wrong way,” she said. “Not just for any old reason, but with justification.”

Even so, Glenda’s advocacy is grounded in culture first. “If you are a community member, of course I advocate for you as a Gullah/Geechee person in a Gullah/Geechee community,” she said. “But if you decide that you want to sell your property, I advocate for culture, which means I have to discourage you from selling your property.”

It’s a challenging position, one that often puts her in opposition to neighbors. “It means that even though you can have a short-term benefit by allowing something into our community that would not be compatible,” she explained, “I have to speak to you in favor of community, in favor of culture.”

And the pressure never lets up. Because every zoning battle rests on a longer history: “We were just dealing with that,” she said. “Land use and zoning—major. The truth of the matter is that… largely because of redlining and federal practices with respect to the interstate highway system… the roadways and highways grew through Black land wealth.”

That’s where the Trust focuses its energy—bridging tradition and legal infrastructure. “We want to do the two things together,” Glenda said. “We can have the title cleared—and now we have a succession plan right there to jump in. Because if you let there be a lapse or a lag, then it’s an open invitation for being taken.”

The 200 Voices Project and Intergenerational Memory

Logo for the 200 Voices Project

Legacy doesn’t just live in buildings or documents. It lives in names, voices, and the quiet exchanges between generations. For the GGCCT, the 200 Voices project is a declaration of presence—an effort to center Gullah/Geechee history in a county that has too often overlooked it.

“200 Voices came out of our understanding of Nassau County's history,” Glenda explained, “and their anniversary of 200 years, which they celebrated, I believe, in 2024. And we were pondering this notion that across those 200 years, we have been here. However, our presence in the celebration was not prominent.”

That absence sparked a response. 200 Voices: Reclaiming Gullah/Geechee Places, Spaces, and Narratives was launched not only to amplify the living, but to remember the departed. “We said, not only are we going to have 200 voices,” Glenda said, “but 200 voices beyond.”

Community Connections

GGCCT Fellow Jaya Riley presents at Gullah/Geechee Community Day

It’s an ambitious, multi-part project rooted in honoring ancestors, educating youth, and preserving material culture. It began with Gullah/Geechee Community Day, where the Trust unveiled a miniature exhibit grounded in the 1940 U.S. Census. Led by GGCCT fellow Jaya Riley and volunteer Diane Johnson, the team pulled names, households, and locations from west side communities across Nassau County. Then they put those names on the wall.

“It was our way to introduce the community to this knowledge that... these are the people who made it possible for you to be here,” Glenda said. “You may or may not know their names, but when you see that last name, you're going to know that those are your relatives.”

The emotional resonance was immediate.

“We paid tribute to our elders who are 80 years and older. They were at the board, pointing at the names. I even captured some of the conversations where they're saying, ‘Yeah, that’s cousin so-and-so, and he was two years old at the time.’”

What did it mean for them to see those names? “It’s really affirming,” Glenda recalled them saying. “It helps us to know that we have existed, we contributed something, we've come through a lot.”

The next phase of the project builds on that affirmation through intergenerational exchange. “We’ll be reaching out to elders and pairing them with a young person in their family,” Glenda said. “We’ll start off with maybe seven to ten [pairs] and bring in a professional to help them navigate genealogical records… so the elder can work with the younger person to walk through their lineage even further back.”

Community Names for Ancestral Names Project

The goal is more than just documentation. It’s about equipping the next generation to carry forward what might otherwise be lost. “That is to equip the young person with the tools to carry on the history that they might not otherwise have the information to carry on,” Glenda explained.

The third phase moves from names to structures—specifically, buildings constructed by Gullah/Geechee hands on the western side of Nassau County. While some may dismiss them as “just old houses,” Glenda sees something more profound: “That’s African technology.”

In partnership with architectural designer and Franklintown descendant Philip Jefferson, the Trust is scanning, documenting, and analyzing these vernacular structures. “We will be making printouts and doing some type of perhaps three-dimensional models,” she said. “And [Philip] is going to provide us with some comparisons between the skill sets that we had as Gullah/Geechees and how that may relate directly or indirectly to our African heritage and some of the trade ability that our ancestors had.”

The work is a reminder that cultural memory isn’t abstract—it’s built into beams and floorboards, names etched into census records, oral stories passed from elder to youth. “We are taking every opportunity that we can,” Glenda said, “to remind people, as Queen Quet says, ‘We da beenya. And we ain’t gwon.”

“We’re Sowing Seeds for Something Bigger”: The Vision, the Fight, and the Future

As the Gullah/Geechee Cultural Community Trust continues to grow, so too does its vision, rooted in reverence, driven by resolve, and anchored in legacy. When asked what she hopes the Trust will become, Glenda didn’t hesitate.

“What I hope for the Trust is that in five years we will have recovered most, if not all, of the burial areas that are on our target list,” she said. But her vision doesn’t stop with gravesites. It stretches wide into education, sustainability, land use policy, and generational empowerment.

“We also hope for a place where we can share our history and culture with the community,” Glenda continued, “and how it relates to even climate resilience and environmental work and workforce development around forestry. Forestry was an area that our ancestors were heavily engaged in, and we’d like to reintroduce that to the young people.”

Glenda-Simmons Jenkins and Kathie Carswell at Franklintown Church

That sense of continuity—from the past to the future—is central to how Glenda thinks about leadership. “Part of what I want to see happen is for us to understand the limits of what we can bring in our generation,” she said, “and have no problem in allowing the mentorship that we’ve done to go so far so that the young people can step into a role.”

That future includes policy victories as well: “I think it would be awesome if we are able to secure appropriate land use and zoning policies for our community so that we don’t have to just constantly challenge every new zoning trickery that happens.”

But beyond the policies, it’s about identity. “A policy that speaks explicitly to us and our culture,” Glenda explained, “is going to be a unifying measure that will position us differently—with each other and with the community we’re in.”

In doing so, she believes the narrative will begin to shift—from marginalization to presence, from colonial oversight to self-definition.

“It will speak very powerfully to us about who we are and what we bring to the formula that is this community,” she said. “It’s a way to shift the narrative from some of this more colonizer perspective… to we to be in this community. And how we, despite all of the challenges, have retained and maintained our culture and our history.”

Her dream? A replicable model of governance and advocacy grounded in the Gullah/Geechee experience—one that future generations can build on.

“If we can build a model that can be used in every governmental policy as it relates to the Gullah/Geechee community… if we can get that, I say that we’ve done something.”

But it also requires breaking the fear that still surrounds political engagement. “What we don’t want is our community to be afraid of local government,” Kathie said. “We want them to be involved in the processes that impact them.”

And for Kathie, the root of that drive goes back generations. Or rather, to the generation she never got to know.

“When I look back over my great-great-grandfather’s record… I don’t know where it came from,” she said quietly. “I don’t know where he was born. I don’t know where his footprints went. I don’t know what his struggles were. I don’t even know what he looked like.”

That silence fuels her.

“I still want to know,” she said. “Because I want to know where my fight came from. I want to know where this determination came from—because it came from somebody who was determined. I’m in it for that. I’m in it for that.”

Follow and Support the Gullah/Geechee Cultural Community Trust

Website: https://www.gullahcommunitytrust.org/

Instagram: @gullahtrust

Email: Contact@gullahcommunitytrust.org