(S1E6) Freedom Was the Curriculum: 163 Years of the Penn Center

How has the Penn Center functioned as a hub for Black freedom and cultural preservation for over 160 years?

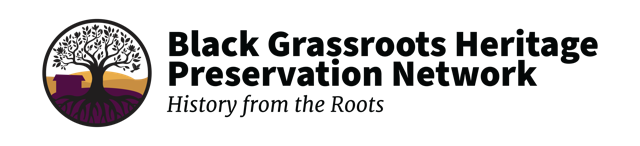

The Origins of the Penn Center: Education for Freedom

Exhibit Signage in the Penn Center’s York W. Bailey Museum

Tucked into the moss-draped landscape of South Carolina’s Sea Islands, the Penn Center sits quietly on 500 acres of land that holds generations of stories—stories of defiance, survival, and Black cultural brilliance. But this is no ordinary historic site. It’s one of the oldest Black educational and cultural centers in the U.S., founded in 1862 as the Penn School during what’s known as the Port Royal Experiment.

Back then, Union troops had just taken control of the South Carolina Lowcountry, and thousands of formerly enslaved people were left behind on abandoned plantations. A group of Northern missionaries, teachers, and reformers from places like Boston, Philadelphia, and Baltimore came south to help support the transition from slavery to freedom. They were called Gideonites. They brought books, tools, and a bold belief that education was essential for liberation.

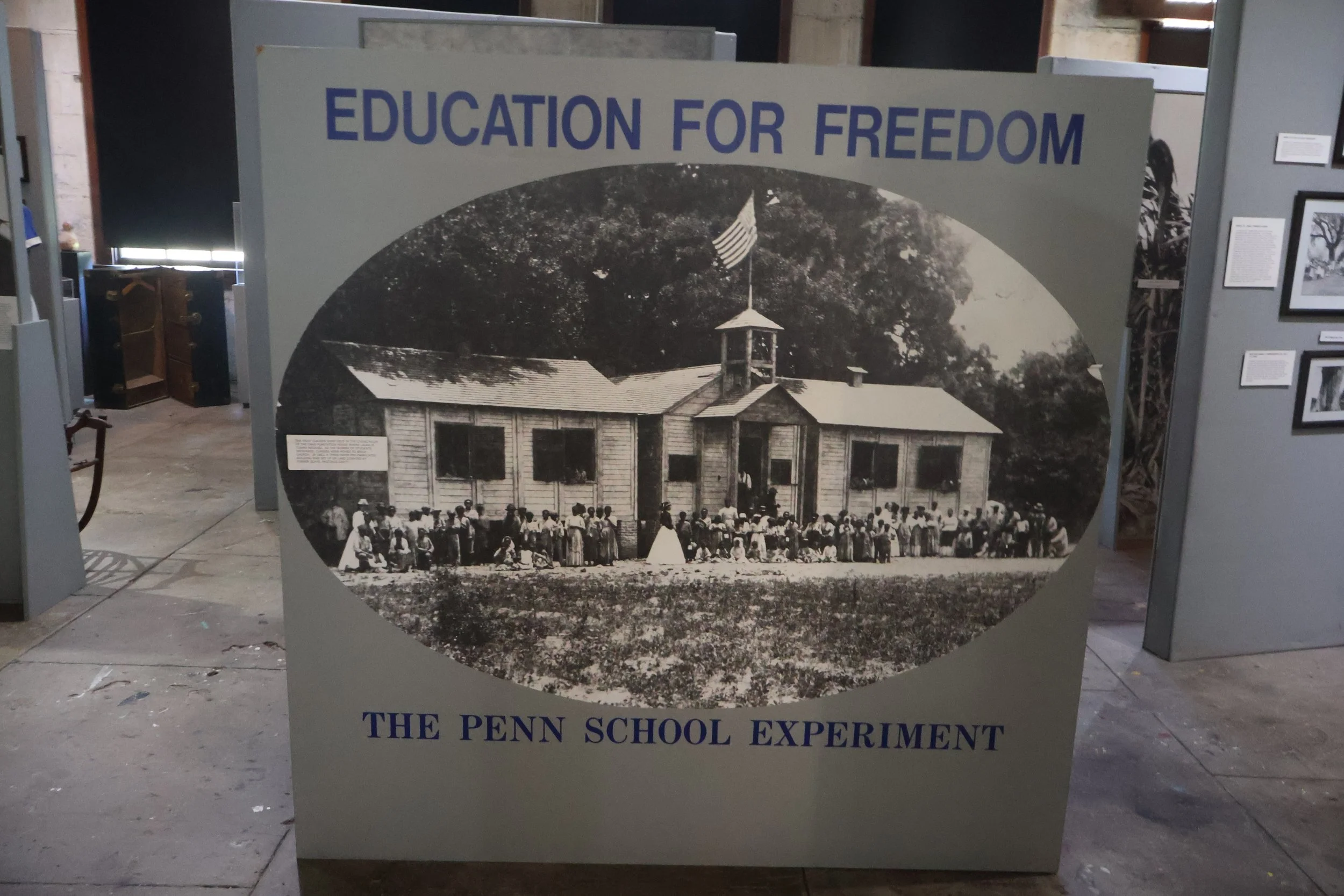

The Rev. Jesse Jackson, from left, Joan Baez, Ira Sandperl, Martin Luther King Jr., and Dora McDonald (King’s secretary) are photographed at a Southern Christian Leadership Conference staff workshop held at the Penn Center on St. Helena Island in 1966. Courtesy of the Penn Center.

Dr. Robert Adams, the Penn Center’s executive director since 2023, describes the era with deep reverence. “The Center started during what we call the Port Royal Experiment,” he said, recalling how those early educators arrived to provide “education and other social supports to transition African Americans from enslavement to freedom.” For Adams, who holds a PhD in anthropology, the work at Penn isn’t just historical—it’s personal. “I'm interested in Black history and culture as a means of… a foundation for liberation,” he explained. “There is no better place to pursue Black liberation than at the Penn Center because of its long history of being a site for African Americans gathering to map out the future of Black freedom.”

That history runs deep. The campus was once a meeting place for Robert Smalls, the formerly enslaved man who famously commandeered a Confederate ship and later served five terms in Congress during Reconstruction. Civil Rights icon Benjamin Mays, longtime president of Morehouse College and mentor to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., served as chair of Penn’s board. And Dr. King himself used the center as a retreat space for his Southern Christian Leadership Conference staff—strategizing, resting, dreaming of justice among the live oaks.

Adams sees the Penn Center not just as a monument to these legacies but as a starting point for a broader story. “This is where education for African Americans started during that Civil War period,” he said. “From here, it scaled up across the nation. So in some ways, this is the foundation for what became a Southern education movement for African Americans.”’

Gullah/Geechee Culture in the South Carolina Lowcountry

But the Penn Center’s story can’t be told without the culture that cradles it: Gullah/Geechee. Stretching from the coasts of North Carolina down through Georgia and into Florida, the Gullah/Geechee people are descendants of Africans who were enslaved on isolated Sea Island plantations. That geographic isolation and their deep knowledge of rice cultivation allowed them to retain more of their African traditions than anywhere else in the United States.

Adams puts it plainly: “Gullah Geechee culture, in my opinion, is the early form of African American culture… most forms of African American culture are offshoots of Gullah Geechee culture.”

It’s a culture shaped by both its African origins and its Caribbean connections. “Some of the early settlement came not just through Africa, but through the Caribbean,” he said, pointing to the linguistic patterns, culinary traditions, and spiritual practices that took root here. He even describes the South Carolina Lowcountry as a kind of “northern Caribbean,” shaped by colonial encounters that began as early as 1526 when settlers arrived from Hispaniola, what is now the Dominican Republic and Haiti.

Later, when the English took control, younger sons of wealthy Barbadian families came to establish rice plantations. They cultivated Carolina Gold rice, a prized variety that owes its very existence to the skills and agricultural genius of enslaved Africans.

The land on which the Penn Center sits today is a direct descendant of that history and a powerful rebuttal to it. Spanning 500 acres and featuring 23 historic buildings, the Center now encompasses farmland cultivated in partnership with Black farmers, who cultivate heritage crops—plants passed down through generations, often predating commercial agriculture. But with preservation comes cost.

Diorama of the Penn Center’s 50 acre campus

“We have 500 acres and 23 buildings. Most of our buildings are over 100 years old,” Adams said. “That means that if you want to be a true preservationist, you have to use historical methods and you have to pay real attention to detail… That can be very costly.”

Still, the land holds a promise, one rooted in the unfinished story of reparations and self-determination. “Land is an important part here,” he added, “because the whole idea of 40 acres and a mule started here in the Port Royal Experiment.” In that era, newly freed people were allowed to purchase confiscated land and surplus mules—tangible steps toward freedom that remain unmatched in U.S. history.

Fighting for Survival and Sustainability in the 21st Century

“In the 40s and 50s, it was mostly an African-American island. Now, I think the Gullah Geechee population is like 3%. It’s nothing wrong with having a tourist enclave like Hilton Head. What is wrong is when different communities get pitted against each other… that we can only have a tourist development if we displace Black people. That’s wrong.”

Penn Center Front Office Building

For Dr. Robert Adams, preserving Gullah Geechee heritage isn’t simply a matter of memory—it’s a matter of survival. On South Carolina’s St. Helena Island, where the Penn Center serves as both cultural anchor and historical touchstone, the work of preservation collides daily with the pressures of development, tourism, and erasure.

A key line of defense, Adams explains, is policy backed by people. In 1999, Beaufort County passed the Cultural Protection Overlay (CPO), a zoning ordinance explicitly designed to preserve the island’s rural character and protect Gullah Geechee culture. The result of tireless organizing, it was a line in the sand against gentrification and cultural erasure. “That can only come about through the active participation of local residents,” Adams noted. But policy alone isn’t enough. “That can only come about through the active participation of local residents who were opposed to gentrification,” Adams said.

De Nyew Testament, a Bible written in Gullah/Geechee Creole

It’s a hard-won lesson, shaped by proximity and contrast. Just across the bay from St. Helena lies Hilton Head Island—once a predominantly African American island, now transformed into a luxury destination. “In the 40s and 50s, it was mostly an African-American island. Now, I think the Gullah Geechee population is like 3%,” Adams said. “It’s nothing wrong with having a tourist enclave like Hilton Head. What is wrong is when different communities get pitted against each other… that we can only have a tourist development if we displace Black people. That’s wrong.”

It’s also shortsighted. As Adams points out, Gullah Geechee culture isn’t just historically significant—it’s a primary reason people visit the Lowcountry. What’s at stake, he emphasized, isn’t just physical space. It’s a legacy. “If we get rid of it [Gullah/Geechee culture], what are they going to come for?” he asked, pointing to the tourism industry’s paradoxical relationship with Black culture: eager to market it, reluctant to protect it.

Among the most urgent and complicated threats to land retention in Gullah Geechee communities is heirs’ property—a legal limbo that continues to unravel generational wealth and destabilize cultural continuity. “One of the big challenges here is heirs property,” Adams explained. “That property is not outright owned or doesn't have a clean title. It's owned by a number of descendants of the original deed holder.”

Dr. Robert Adams, Executive Director of the Penn Center on the Significance of Gullah/Geechee Culture.

Without a clear title, descendants often can’t build on the land, borrow against it, or even agree on repairs or upkeep without consensus from multiple relatives. Something as sacred as inherited land ends up stuck in bureaucratic limbo. To confront the problem, the Penn Center has stepped in as both educator and advocate. “We host different seminars and bring in speakers to talk about heirs property,” Adams said. “We also bring in sometimes legal services.”

Even with expert advice, one of the most common—and avoidable—threats is painfully simple: unpaid taxes. It doesn’t take a court battle or a development scheme to uproot a family’s land. Just a missed payment.

Because no single owner holds title to the land, families have to coordinate who pays what. “Oftentimes taxes go… delinquent because nobody's decided that,” he noted. The result can be devastating: a $200 tax bill left unpaid can spiral into a loss of land worth tens of thousands. “There's nothing worse than somebody forgetting to pay a $200 tax bill and losing thousands of dollars worth of valuable real estate,” Adams emphasized, “because they didn’t coordinate well.”

And once land is lost at a tax sale, it’s not just the family that suffers—it’s the whole cultural landscape. “It provides beachheads for people to undergo development activities that are contrary to the preservation of Gullah/Geechee culture and place,” Adams warned.

That’s why the Penn Center created a grassroots fund to help. “We do it as a kind of a revolving fund,” he explained. Families contribute what they can upfront, and after receiving assistance, they pay the funds back, helping replenish the pool for others. “We’ve done a lot to help save people’s lands, and that’s an important part of our community action.”

It’s not charity—it’s continuity.

This work reflects a long tradition of self-reliance and collective care that has anchored St. Helena Island for generations. Mutual aid, Adams emphasized, isn’t just a feel-good phrase here—it’s a survival strategy.

With persistent poverty and food insecurity, even a simple dock becomes a lifeline. “We have a dock and we're on the water,” he said. “So we allow community members to come and get fish, crab, and shrimp off our dock.”

It’s a quiet act of solidarity. But for many, it means everything. That force—quiet, rooted, and deeply ancestral-is what animates the work of the Penn Center and its surrounding community. It’s what makes preservation here not just a task, but a testimony.

Legacies of Grassroots Leadership and Community Resilience

Dr. Robert Adams, Executive Director of the Penn Center on the Significance of Black Culture to American History.

In the present struggle for cultural survival and sustainability, if the Penn Center’s historic buildings and live oaks could speak, they’d likely echo what people on St. Helena Island say every day: “People stand up and speak out.” That simple phrase, shared by Executive Director Dr. Robert Adams, cuts to the core of what makes this Lowcountry community extraordinary.

While the Penn Center was founded during the Civil War by Northern missionaries, Adams is quick to clarify that the true power of this place has always come from the people who were already here. “It isn't just a story of missionaries saving a local population,” he said. “It is actually a population that had already been exercising its agency.”

Long before terms like “grassroots organizing” entered the mainstream, residents of St. Helena were practicing what Adams calls “democratic participatory leadership.” He describes a deeply rooted tradition of mobilization: people taking an active role in shaping their futures, defending their land, and resisting exploitation on their terms.

So when a developer recently tried to slip in a golf course development—despite the island’s Cultural Protection Overlay, which explicitly prohibits such projects—the community didn’t just raise concerns. They showed up. “People mobilized,” Adams said, recalling how county council meetings overflowed with locals voicing their opposition. “So many people came to the meetings. So many people stood up to say they didn’t want it. So many people spoke out.” The result? The developer backed off.

That kind of organized, vocal resistance isn’t a one-time event. Back in the 1980s, a similar campaign erupted when the state tried to expand the island’s highway into a five-lane thoroughfare. Residents pushed back, successfully preserving the road’s original three-lane configuration and keeping the rural character intact.

These victories didn’t happen by accident. They reflect a community with deep civic consciousness—one that refuses to be sidelined.

For him, that resistance defines the Gullah Geechee experience. “Our story is one of resilience… This whole idea about ‘I’m still here,’ despite 500 years of efforts to erase, eradicate, and dominate.” And that resilience isn’t abstract—it’s embodied daily in how this community shows up, speaks out, and safeguards its culture. As Adams sees it, St. Helena Island isn’t just preserving the past. It’s shaping a future where Gullah Geechee people remain “a potent force in this country, a potent shaper of the future of this country.”

Global and Local Partnerships: The Past and the Future

If the Penn Center is rooted in history, it’s also actively shaping the future through global partnerships, intergenerational dialogue, and an unwavering commitment to youth. For Executive Director Dr. Robert Adams, this balancing act of honoring local tradition while engaging the world is a dynamic process. “It’s almost like playing an accordion,” he said. “You’ve got to sort of push it in and then pull it back out when you’re doing the larger stuff.”

That rhythm—between local activism and global visibility—has strategic benefits. “You need those national and international relationships to help you on the local level,” Adams explained. International media coverage, for example, raises the stakes for developers or policymakers who might otherwise push through “unpopular and undemocratic proposals” under the radar. At the same time, large-scale funders and cultural institutions value Penn’s deep grassroots reach. “Some of our national partners like the fact that we’re working at such a grassroots level because oftentimes they don’t get to impact at that level.”

One of those partners is the Mellon Foundation, which Adams credits for helping to build a preservation ecosystem across the Gullah/Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor. “They’ve been working across the Lowcountry to seed an ecosystem of Gullah Geechee preservation work,” he said. “And our legacy is being able to work between that tension of local and national and global.”

He calls it a glocal approach—global and local, simultaneously. That philosophy fuels his desire to connect with preservationists across Africa. “We are the outcome of transnational global movements and histories,” Adams said. “And our work has to reflect that.” Even while helping families hold onto land here on St. Helena, the Penn Center is laying the groundwork for cultural exchange, knowledge sharing, and historical reckoning across continents.

Penn Center Campus

This work includes deep ties across the corridor and beyond. Penn has collaborated with Sapelo Island in Georgia, particularly with the family of the late Cornelia Walker Bailey (1945-2017), a legendary cultural preservationist. “We’ve gotten together with her son and some other folks to figure out how to honor that legacy,” Adams said. “But we’re always working across the Lowcountry.”

Adams describes how Gullah/Geechee communities influenced cultural expressions across the South and even into Oklahoma, Texas, and northern Mexico. Adams points to the ways Gullah/Geechee people intermingled with Native Americans, becoming part of the Seminole communities in Florida. He recounts stories of descendants in northern Mexico who, despite no longer speaking English, still sing Gullah spirituals, passed down across generations. “So we’re not surprised when we find a 93-year-old in Northern Mexico who sings Gullah spirituals… because she got it from being a descendant of a Gullah Geechee community.”

St. Helena, he notes, is one of the origin points in this larger diasporic movement. Much like 1619 in Virginia, the South Carolina Lowcountry holds foundational importance in the story of American democracy and Black cultural formation. “It’s one of those starting points… so we can understand our long history and our long engagement with forming this country.”

“Peace Tree” planted by the United Nations on the Penn Center Campus

The Penn Center’s global significance also hasn’t gone unnoticed. In 2024, the Penn Center was added to UNESCO’s network of Sites of Memory of Enslavement and the Slave Trade, joining a constellation of historic places across Africa, Latin America, and the Caribbean, a global network of locations tied to the transatlantic slave trade. “These are important markers,” Adams said, “where we can reflect on this tragic past, but we can also reflect on our valiant efforts to resist enslavement and its negative effects.” It wasn’t the first time the world had acknowledged this small island’s outsized influence.

Back in 1925, Nicholas GJ Ballanta (1893–1962), a scholar from Sierra Leone, traveled to St. Helena to collect and document spirituals sung by Gullah communities—songs he later linked to West African traditions, and published in The St. Helena Island Spirituals. “We’ve always been kind of like a global place,” Adams reflected. In 1955, the United Nations even planted a “Peace Tree” on the Penn Center’s campus to mark its tenth anniversary, cementing the site’s symbolic role in global peace and memory.

And perhaps no area of that collaboration is more vital than engaging youth. Adams’s vision as a new executive director is grounded in opening up the horizon for younger generations. “We want to take young people [abroad],” he said, “so they can use these global connections as a way to create a new sense of self.” Too often, he noted, youth become disoriented by limited local opportunities or internalized hopelessness. “Sometimes young people can get lost in the sense of being a youth… but sometimes you have to open their minds up—through direct experience—to how divine they are.”

That commitment to youth is rooted in legacy. In the late 1980s, Penn’s then-director Emory Campbell led a historic delegation from St. Helena to Sierra Leone. “They called it a homecoming,” Adams said. The journey was captured in the documentary Family Across the Sea, which helped spark a reciprocal relationship. The then president of Sierra Leone, Joseph Saidu Momoh (1937-2003), even visited Penn.

That sense of connection—rooted, diasporic, reciprocal—isn’t just symbolic. It’s a practice of solidarity. Adams, who has lived and worked both in Africa and throughout the diaspora, sees enormous potential in these exchanges. “There’s so much to learn from Africa,” he said. “And I know a lot of things that they’re doing there that could benefit us here.”

From indigo farms in St. Helena to cultural exchanges in Sierra Leone, from youth programs to post-conference excursions, the Penn Center continues to serve as a bridge between past and future, local memory and global movement.

Its accordion-like rhythm keeps stretching outward and folding back in—always in tune with the land, the people, and the promise.

Follow and Support the Penn Center

Website: https://www.penncenter.com/

Email: Info@penncenter.com

IG: https://www.instagram.com/penncenter1862/?hl=en

X/Twitter: https://x.com/PennCenter1862

FB: https://www.facebook.com/PennCenter1862