(S1E7) We Just Wanted to Be Free: The Safe House Black History Museum

How do faith, dignity, self-respect, and intergenerational land stewardship inform both survival and freedom?

Sheltering Martin Luther King Jr.: A Safe House in the Line of Fire

Pastor Kervin Jones, Executive Director of the Safe House Black History Museum

In Greensboro, Alabama, just off a quiet street, stands a house that once shielded Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. from the deadly threats of the Ku Klux Klan. But for Kervin Jones, the Executive Director of the Safe House Black History Museum, the story doesn’t begin or end with King. It starts with a community that dared to protect him, and with a woman who believed ordinary people’s sacrifices deserved just as much reverence.

“We want to remember Dr. King being here,” Jones says, “but also all the foot soldiers. People who will never be famous worldwide, but we want to celebrate them and remember them.”

March 21, 1968. Dr. King was in Greensboro, speaking at St. Matthew’s Methodist Church. The Ku Klux Klan was already circling. According to Executive Director Kervin Jones, “they got word into the church that they were gonna kill Dr. King that night.”

What happened next reads like something out of a spy novel—but it was real.

“They sent decoys,” Jones recounts. “Convoys of cars went out in different directions—toward Tuscaloosa, south, west—all to throw people off. But they brought Dr. King here, to this house.”

Exhibit text featuring a quote by Theresa Burroughs.

The house belonged to the Burroughs family. The late Mrs. Theresa Turner Burroughs (1928-2019), the founder of the museum and a fierce local activist who had been deeply involved in the movement, couldn’t shake the weight of that night. For her, this wasn’t just a house. It was sacred ground. Burroughs was there the night Dr. King had to be hidden in the house that is now the museum. “That night,” she remembered, “we had Reverend Shuttlesworth, T.Y. Rogers, Hosea Williams, Albert Turner… And Martin was the slowest person. Slow to walk, slow to talk. He was still there speaking when someone burst into the church: ‘Don’t take him down 14. The Klan’s waiting for him.’”

Churches were burning. Gunshots cracked the sky. But the people of Greensboro made a choice. They brought Dr. King here. “Every man in the neighborhood grabbed his gun and surrounded this house. Martin was inside, asleep. He didn’t even know what was happening outside.”

Black men stood guard with shotguns in hand. “Even though Dr. King was nonviolent,” Jones says, “they said, ‘Not tonight. The Klan won’t take him in Greensboro.’”

King made it safely through the night. They woke him around 4 a.m. and rushed him out—first to Selma, then Montgomery. Within two weeks, he was dead—assassinated on April 4th, 1968, in Memphis, Tennessee.

Continuing Her Legacy

Mrs. Theresa Turner Burroughs, founder of Safe House Black History Museum (1928-2019)

“She just wanted us to be free,” Jones says of the late Theresa Burroughs. “Tired of being treated like second-class citizens. Couldn’t vote. Couldn’t participate economically. But she carried herself with dignity and pride. She was a leader.” In the years that followed, Burroughs transformed the house into a museum, not just to remember King, but to honor the unsung. “We must remember her vision,” Jones says. “This museum is about what the local people contributed—their sacrifices, their stories, their courage.”

Even now, the museum is still collecting and identifying artifacts. Some locals remain unaware that they hold valuable pieces of that history. “Photos, memorabilia—they don’t realize how important it is for us to preserve it, to have a place that tells our history.”

Jones never expected to run a museum. He was an educator and a pastor. But he felt the pull of history, and when the museum board asked if he’d take on the role—unpaid—he agreed to volunteer. “I thought I’d do it for a year,” he laughs. “It’s been four.”

Running a grassroots museum, he says, is like pastoring a small church. “Same personalities, same blessings, same headaches. We’ve got to make a dollar go two miles. But it matters—especially now. Because there are people who’d like to erase our history. Make us ashamed of who we are.”

The museum’s collection includes intensely personal artifacts: the very bed where Dr. King slept that night, his traveling trunk, and much more. “They help visitors remember that Dr. King was a man,” Jones says. “No cape. No superpowers. Just a conviction—that his kids deserved a future, just like everybody else’s. And he stood up for that.”

“We haven’t gathered all the material yet,” Jones says. “Some people are just now starting to realize the significance of what their parents did.” And that’s the point. Preservation isn’t just about the past—it’s a living process. It’s as much about keeping history alive as it is about honoring what happened. It’s about reclaiming the right to narrate your own story, even when others have tried to overwrite it.

What Words Can’t Hold: Memory, Exhibits, and the Unspoken Weight of Black Survival

“I had so many pictures. They need to be seen by even the unborn generation. We have nothing to show for our participation in the movement. We needed something positive you could see. Something you could feel when you walked in the door.”

Photograph of Safe House Black History Museum interior

In a museum filled with living memory, faded photographs, and salvaged objects that carry the weight of struggle, some things speak louder than words ever could. Kervin Jones knows this well. “Images for a lot of people say what words cannot say,” he reflects. “You can read about it—but to see the photograph, or hear Ms. Burroughs describe standing next to someone whose blood splattered onto her dress—that just takes on a different kind of meaning.”

Among the museum’s rare collections are unpublished photographs of the Greensboro marches and events like Bloody Sunday. These images, he says, bear witness to the fact that it wasn’t just icons of the civil rights movement who risked everything—it was everyday people. “Just average people, going to work every day, getting their heads bashed in.” Those visuals, frozen in time, do something that narrative alone cannot: they humanize the fight for justice in deeply intimate ways.

Executive Director Rev. Kervin Jones, on the impact of civil rights activism on mental and physical heath.

And behind the images lie stories that aren’t always told—not just of marches or protests, but of emotional toll and generational trauma. “I just wonder,” Jones says quietly, “if those men and women who suffered through Bloody Sunday—did they develop PTSD? No one ever asked. How did that affect them long-term? How did it affect the women sending their husbands to work, their children to school, not knowing if they’d return?”

His mother, he reveals, carried such a burden. When schools first integrated, three of her children had to walk a mile through the woods after getting off the bus. “She would sit on the porch with her .22 every day,” he recalls, “waiting to hear her children scream. That had to be a very stressful thing for her.” She later died from heart disease, and he often wonders whether the chronic stress of those years contributed to her decline. “It’s now a medical fact,” he notes, “that stress in early life can manifest as heart issues in later life—just like a poor diet. So when we say Black women have heart issues from diet, maybe it’s the stress of having to send their kids out into danger every single day.”

A photo exhibit of civil rights movement foot soldiers in Greensboro, AL.

These realities hit hard for museum visitors, especially when they encounter the physical artifacts—raw cotton, for instance, or the mugshots of young children arrested for protesting. “They’re just amazed,” Jones says. “When they realize how much cotton had to be picked, how brutal that labor was, it starts to settle in.” He often points to a mugshot of a boy and tells young visitors, “Look at his birthday—he’s your age, or younger. Could you go out and stand in the hot sun and get arrested just for the right to vote?” That’s when it clicks. “It really brings to reality that it wasn’t so long ago. And if they could do it, why can’t you?”

In this way, the museum doesn’t only preserve—it provokes. It challenges people, especially younger generations, to see themselves as capable of making history, too. One young man, Jones recalls, stopped in on business and noticed his grandmother’s photograph on the wall. “He told me, ‘I’ve never voted.’ But after seeing that—he said he’d go register.”

What ties it all together is the power of personal stories. The museum’s exhibits are grounded not in abstract facts, but in lived experiences—oral histories, family memories, and emotional testimony that bridge the gap between then and now. Jones admits that he was even more surprised to learn, after becoming Executive Director, that two of his own siblings had been present the night Dr. King hid at St. Matthew’s Church. “I didn’t know until later in life,” he says. “It was so traumatic, people just didn’t talk about it.”

That silence, he believes, is part of the harm. “We fail to tell the story because we don’t talk about the trauma. But sharing becomes therapeutic. My mother didn’t tell me about sitting on the porch with her rifle until after her first open-heart surgery. And I think—how much of our pain have we kept to ourselves?”

A photo exhibit of civil rights movement foot soldiers in Greensboro, AL.

The stakes of telling these stories are high. “Other people will tell us our stories aren’t important,” Jones says. “It dehumanizes us. But when we tell it—what our families endured—it affirms that it was important. It is worth repeating.”

In the local context, that fight for historical visibility is ongoing. “There’s not a single statue of an African-American in Greensboro,” he says. “But you’ll see other statues all over, streets named after other people. And in some places where there is a Martin Luther King Boulevard, it’s always in the poorest part of town. That tells us something—tells us we’re not worth much. That’s why it’s so important that we tell our own story.”

That commitment to community-driven storytelling is also what drew the museum into partnership with Auburn University’s Rural Studio. The Rural Studio, a renowned architectural design program, helped create contemporary exhibits like Identity. “I think Ms. Burroughs, because of her stature, got them to come here and work with us,” Jones explains. “It wasn’t just about architecture. It was about community. About public service.”

That spirit extends to the art within the museum’s walls—paintings, sculpture, and mixed media that speak not only to the Black freedom struggle nationally, but also to the hyperlocal story of Greensboro. For Jones, art becomes another language of liberation. “Some people don’t talk. They don’t sing. But they still have a story to tell. And they tell it through painting, through drawing, through sculpture.”

As a pastor, Jones may be a natural speaker, but he’s just as moved by the quiet power of a canvas or a hand-carved figure. “We all communicate in different ways,” he says. “But at the end of the day, the message is the same: We were here. We mattered. We still do.”

Where Art Speaks, Memory Stirs, and Humanity Refuses to Be Denied

Interior of the Safe House Black History Museum Community Room and Gallery

The Safe House Black History Museum isn’t just a repository of artifacts—it’s a space that invites creative expression, community reflection, and intergenerational dialogue. For Executive Director Kervin Jones, the art room in the museum isn’t just a corner of canvases and paint—it’s a vital part of what makes the space alive. “If art is your thing,” he says, “we want a place where you can do it.”

But more than practice, it’s about conversation. “Often the artwork spurs discussion. Let’s talk about this piece you created—or this piece someone else painted. Maybe it’s their version of Bloody Sunday. What do you see in that?” Art becomes an entry point. A way for young people and elders alike to access emotions, memory, and meaning that can be hard to reach through words alone. “It brings thoughts into our minds—and then we can share our feelings.” The museum is not just a place for artifacts. It’s a living, breathing cultural hub. Local artists contribute work. Community members gather for book signings, dialogue, and healing.

There’s even a small studio for children to create art—some draw the civil rights struggles they’ve learned about, others their hopes for the future. “Art helps people say what words sometimes can’t,” Jones notes.

Executive Director Rev. Kervin Jones on the impact of Black women in the civil rights movement.

Two documentaries have emerged from this work: Let Us Praise the Foot Soldiers Who Came Before Us, which honors those who marched and organized during the civil rights movement in Alabama, and Let Us Give Praise to the Women Foot Soldiers of Hale County, Alabama which centers the vital yet often overlooked role of Black women in the struggle for justice. Executive Director Kervin Jones came on board just as the second film was wrapping, so he can’t speak to their production process, but he can certainly discuss their meaning. That, he knows well. “We celebrate the men, and surely we should,” he says. “But the women—it took strong women.” He names Fannie Lou Hamer in Mississippi, and the countless mothers, wives, daughters, and sisters who held families together while fueling a revolution. “If you knew that history,” Jones stresses, you wouldn’t hesitate to vote for a Black woman today,” he says, referring to Kamala Harris.

This emphasis on sharing extends beyond the gallery walls. The museum has grown into a vital gathering space for the Greensboro Depot Historic District and the broader Black community. “It’s somewhat of a hub,” Jones says. “We’ve had book signings, African American artists coming to share their work, people just coming in to have conversations about what’s going on in the community. Past and present.” For many, it’s the first place they’ve felt truly seen—and for those unfamiliar with the neighborhood’s role in the civil rights movement, it becomes an awakening.

“This community played a significant role in the success of the civil rights movement,” he explains. “It’s not a large space, but people come in and they remember. They leave changed.” Some register to vote. Others start asking new questions about their family history. That kind of shift—from disengagement to involvement—is, for Jones, the museum’s quiet power.

Donated animal feeding through by which enslaved children were fed.

When asked what exhibit speaks to him most personally, he doesn’t hesitate. “The trough,” he says. A large wooden basin sits near the front of the museum. At first glance, it might seem like an old farm tool. “The person who donated it said it was a dough bowl,” Jones explains, “but it’s too big for that. History tells us otherwise.”

Frederick Douglass wrote about it. So did others who survived slavery. Toddlers, too young to understand the world around them, were fed from animal troughs. “The plantation cook would pour whatever she had into the trough, ring a bell, and children would come running—eating like animals,” Jones says, his voice quiet with weight. “I have a farm. I know what it means to feed animals that way. It’s just so dehumanizing.”

That image—Black children being fed like livestock—still haunts him. “From an early age, that’s been the story of slavery, of Jim Crow,” he says. “And even now, with all the pushback against what they call ‘wokeness’ or DEI—it’s just another way of saying we’re not quite human.”

He shakes his head. “In church lingo, I say: it’s not a new devil. The devil just put on a new dress.”

For Jones, that continuity is what makes the work of the museum so urgent. It’s not ancient history—it’s a living legacy. The echoes of slavery and segregation still reverberate through underfunded schools, health disparities, and political silencing. “Our school,” he says, referring to his childhood in the Jim Crow South, “was never as good as the white school. It didn’t get the same funding. The message was: you’re not quite good enough.”

And yet, the museum exists as an answer to that lie. A space that insists on dignity, worth, and memory. Through art, photographs, oral histories, and even the pain of a wooden trough, it tells a different story—one where Black lives are not just remembered but honored. Not just visible, but vital.

But it’s not just the items—it’s what they awaken.

“When visitors see cotton and realize how much someone had to pick just to meet a quota, or look into the eyes of a teenager in a mug shot, arrested just for marching—they get it,” Jones explains. “These were everyday people, like them. And they made enormous sacrifices.”

There’s also a hauntingly powerful trough on display. While it could pass as a mixing bowl, oral histories point to a much darker origin: enslaved toddlers fed from it like livestock. “That trough reminds me that from an early age, Black people were told we were less than human,” Jones says. “But we were never less.”

“We Were Never Less:” Troughs, Truths, and the Fight to Be Seen

Ku-Klux-Klan Robe donated by a former member to the museum.

That thread of dehumanization runs through much of the museum’s narrative, but one object captures it with visceral force: a Ku Klux Klan robe. It hangs quietly in the museum, donated by a former Klansman who repented for his past and wanted others to see what he once wore in shame. “He came to Ms. Burroughs and said, ‘What I did wasn’t right. I’m sorry. But I want people to see this robe. I want people to understand.’”

Jones recalls other moments when white individuals expressed remorse but were too afraid to act. “A man once told my father, ‘Herbert, you’re right. We’re not treating y’all right. But if I said that in public, they’d kill me quicker than they’d kill you.’” That fear paralyzed many, even those who disagreed with the violence around them. He thinks of Viola Liuzzo (1925-1965), a white mother of five who was murdered while transporting marchers from Selma to Montgomery. Her name still haunts him. “There were people who wanted to help but were forced or intimidated into silence.”

And while Jones hasn’t had former Klansmen personally walk through the museum, he’s encountered their children—the descendants of people who participated in racial terror and came back years later seeking understanding, even healing. Some shared how their parents moved away from the South and tried to forget what they did. One visitor from Birmingham told Jones how ashamed he still feels. As a boy, his white classmates were jumping out of the school windows to go attack Black children during the marches. “He almost went with them. He held his head down. He didn’t speak out. And now, all these years later, he still carries that regret.”

Preserving that kind of truth takes work. And for small Black museums like the Safe House, the challenges are constant, especially funding. “We’re a small community,” Jones says. “We rely on volunteers. Most people here don’t have the time or money to spare. And a lot of grant funding goes to large institutions. We don’t always meet the criteria.”

Signage for the AAACRHSC

That’s what led to the formation of the Alabama African-American Civil Rights Heritage Sites Consortium (AAACRHSC)—an alliance of 20 grassroots civil rights museums and churches across Alabama. Members include, for example, the Bethel Baptist in Birmingham and the Old Ship AME Zion Church in Montgomery. “All of us were struggling to stay alive. So we came together to share resources, encourage each other, and apply for funding as a group.”

The collaboration is beneficial, but securing external funding and support is a delicate balance. “Sometimes people offer money—but they want to take control. And that’s a problem. You can’t understand our story if you haven’t lived it. You don’t get to decide how we tell it.” He offers a warning rooted in painful memory: “Fifty years ago, you might’ve been trying to kill Dr. King. Now you want to direct a museum that celebrates him? No, we don’t want that.”

Autonomy, Jones insists, is non-negotiable. The challenge has always been finding the balance between survival and sovereignty—staying open while staying true. “That tension has been there from the beginning. And it will always be there.”

When asked what advice he’d offer to someone just starting their own museum or community memory project, Jones doesn’t hesitate. “Have a purpose. Know your purpose. Stick to it. Don’t compromise what your goal is.”

His tone shifts slightly, with a blend of conviction and pastoral fire. “Do whatever you have to do that’s right—not necessarily legal. Because remember, much of what the civil rights movement accomplished wasn’t legal when it began.” The law has always been slow to recognize justice.

“And you won’t always be popular for doing what’s right. Dr. King wasn’t always popular in our own community,” Jones reminds. “Even Jesus said a prophet is never honored in his hometown. So don’t wait for approval. If you know in your heart it’s right—just do it. It’s going to be hard. Anything good usually is. But just do it.”

Self-Made and Unbought: The Economic Roots of Resistance

Women like Theresa Burroughs—beautician, activist, and community pillar—used their work not only to support their families but to sustain the movement. Beauty shops and barber shops, Jones explains, were more than just places for haircuts. They were meeting grounds, safe spaces, and funders of freedom. “Independent business owners like Mrs. Burroughs couldn’t be fired for their activism. Ladies were going to get their hair done. Tailors were going to fix clothes. And those independent incomes meant they could stand up for what was right.”

That independence, he argues, still matters. “Entrepreneurship is crucial in our community. If you have your own business, they can’t shut you up. You’re not beholden. You’re free to speak the truth.”

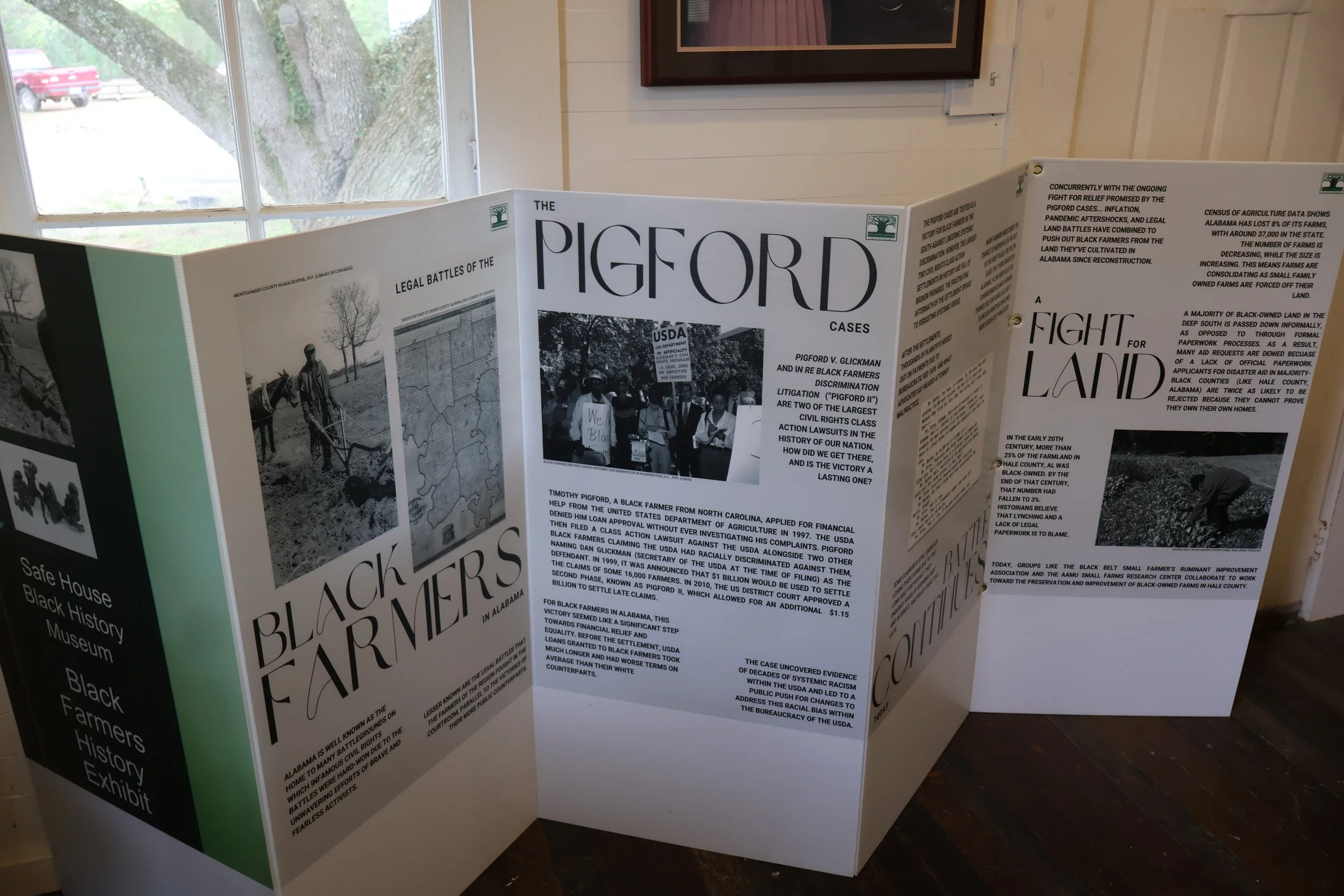

Black farmers exhibit.

The fight for autonomy is personal for Jones, especially when it comes to land. One exhibit in the museum documents the sharp decline in Black land ownership: from 25% to just 3% nationally. That loss, he says, didn’t happen by accident.

During desegregation, he remembers the first question the superintendent asked his mother: Whose land do y’all live on? She responded: We live on our own. That answer mattered more than most people realize.

His family’s land goes back five generations—to a time when his great-great-great-grandfather, a white landowner, enslaved his great-great-great-grandmother. The land has remained in the family ever since. “And we’ve always been told,” Jones says, “‘God’s not creating any more land. Keep the land.’”

“People will offer more than it’s worth just to get you to sell. And once it’s gone—it’s gone.” He tells of a neighbor who sold their land. When their children came back years later to visit their grandparents’ old home, the new owners wouldn’t even let them set foot on it. “There’s a gate across where the house used to be. They said, ‘No. You can’t come here. Not even with permission. We won’t give you permission.’”

He’s seen the patterns. Crooked attorneys. Family infighting. Outsiders waiting in the wings. “When someone dies, there’s always someone ready to buy up the land—cheap. And before you know it, the community has no ground to stand on.”

Some of it, he believes, stems from trauma. “This land represents pain for a lot of folks. They think, ‘Let me just get rid of it.’” Others see taxes as a burden. Or they don’t trust each other—cousins disagreeing over inheritance, deciding to sell and split the profit, not realizing the long-term cost. “It’s heartbreaking,” he says. “People don’t understand what they’re giving up. Or what it does to a community when the land’s no longer ours.”

And that brings him back to the heart of the museum’s mission: to tell this story, not just of civil rights marches and famous names, but of everyday lives, land, and legacy. To tell it honestly. Autonomously. In their own words.

Dreaming Forward: Honoring the Past While Shaping What Comes Next

Safe House Black History Museum Outdoor Signage

Looking to the future, Kervin Jones acknowledges there’s still a lot of dreaming, planning, and building left to do. When asked about the idea of transforming the old cotton gin across from the museum into a community center—or turning one of the nearby shotgun houses into a tech hub—he smiles. “If we reach a conclusion, I’ll let you know,” he says wryly. “But yeah, those are things we need to do, some kind of way.”

He sees those structures not just as abandoned buildings but as extensions of the community’s story. The old cotton gin, in particular, carries deep meaning. “We don’t often recognize how important cotton was to the African American community,” Jones says. “I suspect this neighborhood was once made up of company houses for people who worked in the gin. So that building—it’s a part of who we are.” How exactly to sustain those projects financially is still an open question, but he has ideas. “They’re in their infancy,” he says. “We’ve talked about them. But I think if we keep telling our story and generate enough interest, we’ll find a way.”

For Jones, Greensboro has long deserved recognition as a central site in the history of civil rights and Black resilience. “We’re in the Black Belt. We should be the hub of the movement. Anybody who wants to know about civil rights history—this should be their first stop.” He chuckles, but he’s serious. “I always say, jokingly, that everybody doing something big has roots in Greensboro. If you made it out and you’ve been successful—remember where you came from. Remember what your foreparents endured to get you where you are.”

It’s a point that leads naturally to Dr. King himself. Many people are unaware of the deep connection King had to this area. Just twenty minutes down the road in Marion, Alabama, was the hometown of Coretta Scott King. “Dr. King was in this area a lot more than people realize,” Jones says. “He had to come visit the in-laws no matter what.”

Beyond familial ties, Marion also holds a special place in Black educational history. “That’s where Alabama State University started—at Lincoln Normal School. It eventually moved to Montgomery, but it was rooted here.”

Jones lights up when he lists the others who came from the area: Eugene Sawyer, the second African-American mayor of Chicago, countless educators, pastors, and organizers. “If you don’t remember your roots,” he says, “your fruit will soon die.”

Freedom Lane Hallway, Safe House Black History Museum Interior

For Jones, the work now is making sure that space not only survives, but evolves. That means centering rural Black life, not just as a nostalgic reference point, but as a source of values, strength, and identity. He spoke with the museum’s board president recently, a man whose father and grandfather worked the land in the area. “He said his work ethic came from here,” Jones recalls. “Those farming values—integrity, grit, humility—shaped him.”

And they shaped Jones, too. “Ms. Burroughs’s generation, my parents’ generation—they had to be strong to survive here. And if I come from them, I must be strong too.” That sense of continuity—of drawing strength from your roots—is at the heart of the museum’s philosophy. “You’re working on your doctorate,” he says with a nod. “But it’s because your parents had values. They put them in you. And this Black Belt area? It’s produced a lot of very great people.”

There’s a direct relationship, he says, between historical knowledge and self-respect. “My dad didn’t let people make him feel less than. He taught me to respect myself, to carry myself with dignity. And because of that, I can stand up for what’s right—even if I have to disobey the law to do it.”

At its core, the Safe House Black History Museum tells a story of people who refused to be erased. And yet, many still don’t realize the depth of Greensboro’s contributions to the civil rights struggle.

Jones wants that to change.

“Visit. Contribute. Tell others,” he urges. “We don’t have the budget for big ad campaigns. But we have stories. We have truth.”

And, most of all, they have purpose.

“You don’t have to be famous to matter,” Jones says. “The people in these photos weren’t celebrities. But they had courage. And they changed the world.”

When asked what he wants every visitor—whether local or from out of state—to take away from the museum, he doesn’t hesitate. “That our story matters. That this place matters. And that if we don’t remember our roots, our fruit will die.”

He thinks of his father, who taught him to walk with dignity. Of Theresa Burroughs, who turned her house into a sanctuary and her camera into a witness. Of the generations who endured and endured and still refused to be broken.

“This museum is our story. We built it. We run it. And no one can take it from us,” he says. “As long as we remember who we are, they’ll never erase what we’ve done.”

Follow and Support the Safe House Black History Museum

Website:safehousemuseum.org

Facebook: facebook.com/safehouseblackhistorymuseum

Instagram: instagram.com/aaacrhsc/