(S1E8) Trials by Fire: The Scottsboro Boys Museum

How can we honor justice still in motion without calling it complete?

The Legacy of Shelia Washington

Dr. Thomas Reidy

Executive Director, Scottsboro Boys Museum.

In a quiet corner of northeast Alabama, a modest church stands unassuming but alive with memory. Once home to Joyce Chapel, the oldest African American church in Jackson County, Alabama, it now houses the Scottsboro Boys Museum, a site dedicated to one of the most haunting and consequential legal battles of the 20th century. In 1931, nine Black teenagers—ages 13 to 20—were falsely accused of raping two white women, igniting one of the most infamous legal injustices in U.S. history and a global fight for civil rights.

Dr. Thomas Reidy, Executive Director of the Scotsboro Boys Museum, remembers his first visit. He had driven over from nearby Huntsville, answering a call from the University of Alabama for someone to write a local history of the church. “I knew nothing about the case,” he told me. “It wasn’t what I was studying. My dissertation was on antebellum professionals in Alabama.” But once he stepped inside, his plans changed. “I spent four hours here the first day and didn’t do anything I was supposed to do. I just started reading transcripts of the case and asking questions… I honestly was hooked after that.”

Scottsboro Boy

Haywood Patterson & Earl Conrad

That initial spark would lead him not only to become the museum’s historian but ultimately to step in as director after the passing of its founder, Shelia Washington.

“Shelia is the foundation of this museum,” he said. “We’re all kind of standing on her shoulders.”

Shelia Washington grew up in Scottsboro. As a teenager, she stumbled across The Scottsboro Boy, a 1950 memoir co-written by Haywood Patterson—one of the nine young Black men falsely accused of raping two white women in 1931. The case, which unfolded over nearly a decade, drew international attention and came to symbolize the deep racial injustices embedded in the American legal system. “They became an international cause celeb,” Reidy explained. “Symbols of racial injustice in the American South.”

For Shelia, though, the story was personal. Her brother had been incarcerated at Kilby Prison, the same facility where the Scottsboro Boys were held. His death there, officially ruled a suicide, was something she never believed. That pain, and the unanswered questions it left behind, bound her to the legacy of the Scottsboro Nine.

“She had two dreams,” Reidy said. “One was to set up a museum. The other was to get all the Scottsboro Boys pardoned. Only one of them had received a pardon.”

In 2009, she seized her chance. Joyce Chapel, long shuttered and nearly empty, was up for sale. “There were only four members left in the church,” Reidy recalled. “Shelia got a group together. They started a 501(c)(3), raised money, bought the building and all the land… for $75,000.” Half of that came from a single donor. They had the space. Now they had a mission.

But not everyone in Scottsboro welcomed that mission.

“When you start a grassroots kind of museum,” Reidy said, “especially when it’s one the community, for the most part, didn’t want here... it’s like, ‘Why bring that up? That makes Scottsboro look bad.’”

Scottsboro Boys Museum Executive Director Dr. Thomas Reidy on the memory and legacy of museum founder Shelia Washington.

Shelia Washington (1960-2021), Founder of the Scottsboro Boys Museum

Shelia faced that resistance head-on. “She took all the punches early,” he added. “Certainly the decision makers in the community... there wasn’t really a strong advocate to have this museum here.” Even the museum team struggled at first to explain its value. “I think we had a learning curve with communicating the value of a museum,” Reidy admitted. “The resistance was there at the beginning.”

It was more instinct than strategy at first. “I think it was all gut,” he said. “We knew we needed to do this… but being able to articulate that took time.”

Still, Shelia pressed on. With no formal training—“She had a high school education. That was it,” Reidy noted—she relied on grit, community wisdom, and what he called “street smarts” to bring the right people together. “She knew she needed the right people around her. I think she sensed that I would be somebody good to work with.”

The museum’s complete renovation remained unfinished when tragedy struck. “We had a plan, we had designs done, we raised funds,” Reidy said. “And then the pandemic hit… and Shelia died in 2021. She never got to see the execution of the plans she had signed off on.”

He paused for a long moment. “I love talking about her,” he said quietly, “but at the same time... especially when I’m in her building, it’s bittersweet.”

After Shelia’s passing, Reidy stepped in as interim director. “And then they took the interim away,” he said with a faint smile. “I definitely fell into this. This is not something I would have thought I’d be doing—even after I came here.”

To help visitors understand the trials, the museum now guides them through the world of 1931: a Jim Crow South defined by poverty, segregation, and systemic injustice. “We invite our guests to imagine that they were Black teenagers in 1931,” he explained. “What kind of struggles would they face?”

Digital Kiosk, Scottsboro Boys Museum

Only after grounding guests in that lived reality does the museum walk them into the courtroom. The team’s approach has aimed to blend tactile, visual, and digital elements to create an experience that resonates across ages and generations. Some features speak directly to children: mannequins, interactive displays, and pop-up panels that invite hands-on engagement. Still, this isn’t a museum rich in artifacts. “These were very poor people. They don’t leave anything,” Reidy explains. “It’s not like we have their articles of clothing or their shoes.” Instead, the focus is on layered interpretation and storytelling. The few surviving artifacts, including a courtroom bench, the sheriff’s pistol and holster, and a table from the jail, carry emotional weight. The exhibits are designed to reach beyond objects and into the complexities of the case and its context.

Courtroom Exhibit, Scottsboro Boys Museum

The centerpiece exhibit is a recreation of the second trial, held in Decatur. “It’s the most dramatic one,” Reidy said. During that trial, Ruby Bates, one of the two white accusers, reappeared after going missing—and took the stand for the defense. “She flipped,” Reidy explained. “She said, ‘Nobody touched us… Victoria made me do it.’” That testimony directly contradicted her earlier accusations.

And yet, the jury convicted Haywood Patterson anyway. He was sentenced to death.

But there was a twist. “Two months later, when it came time for Judge James Horton to sign off on the jury verdict, he refused,” Reidy said. “He set it aside with a 23-page statement, saying verdicts need to be based on evidence.” Horton’s action led the state to reindict Patterson yet again.

The story is harrowing. But for Reidy, the museum’s role is about more than recounting tragedy. It’s about helping people see—see what was done, what was denied, and what’s still possible when someone, like Shelia Washington, refuses to let history be buried.

“She had this indomitable spirit,” he said. “Every time I walk in this place, I think about her.”

From Cotton Clubs to Courtrooms: The Cultural Ripple Effect

The Scottsboro Boys case didn’t just echo across Alabama—it sent ripples through Black artistic movements, political circles, and international conversations about justice.

To understand that impact, Reidy places the story in a broader cultural moment. “1931 was probably at the tail end of what we call the Harlem Renaissance,” he said. That period—brimming with poetry, music, and art—was deeply tied to the New Negro movement, which sought to challenge white supremacy through cultural pride and creative brilliance.

“The art that was created during this time,” he explained, “was an expression by artists that Blacks are equal, they have these great talents, and we want you to buy our art.” Black musicians played the Cotton Club to sold-out white audiences, their talent celebrated—but only up to a point. “That never translated, in the eyes of some, into true political and economic equality,” Reidy noted.

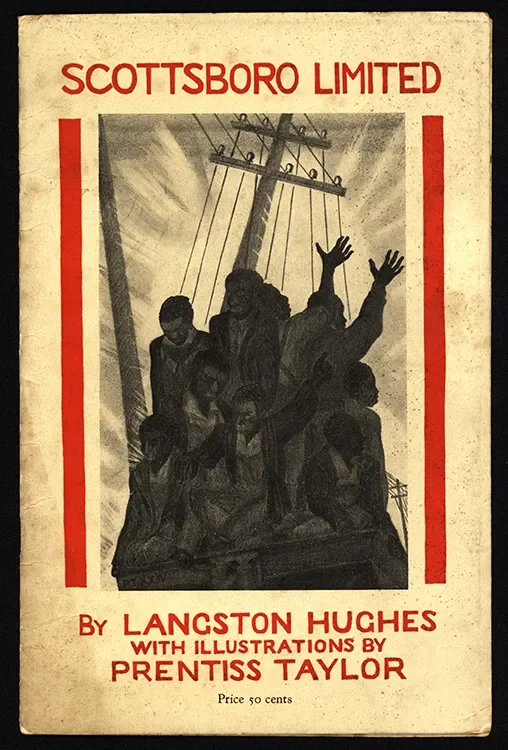

Scotssboro Limited Lithograph, Mary and Leigh Block Museum of Art, Northwestern University, 1992.57

As the 1930s wore on, the Harlem Renaissance gave way to a more radical artistic ethos—one driven by political urgency. Scottsboro became part of that shift. “It didn’t force that change,” Reidy clarified, “but because it came in 1931 when that was already happening, it was a vehicle for many artists to talk about… Now, instead of writing poems to please, it was about telling hard truths.”

Langston Hughes was among the most vocal. After visiting the defendants in Kilby Prison, he wrote four poems about the case. With artist Prentiss Taylor, he created a series of lithographs that were bundled into pamphlets and distributed widely, including tens of thousands of copies sold in the Soviet Union.

“It was revolutionary in some ways,” Reidy said. “It was tied in, in many ways, with leftist, communist demands… Scottsboro was a way for people to look at their own grievances and say, ‘I’m not crazy. Look at what they’re doing down in the South. There’s something wrong with our system.’”

Red Flags and Red Banners: Communism, Protest, and Global Outcry

If that cultural response was expansive, the political response was explosive. The case became a lightning rod for leftist activism and Communist organizing—something the museum has worked to communicate across generational lines.

“In the first two or three years,” Reidy explained, “the Communist Party really was the only legal support for the Scottsboro Boys, through its legal arm, the International Labor Defense.” That involvement wasn’t random. As early as 1928, the Soviet Union had identified the Black Belt—the majority-Black counties of the Deep South—as fertile ground for political mobilization. “They considered the African American as a sovereign nation,” Reidy said, “and because of that, they were going to support it.”

That support was far-reaching. The Party set up headquarters in Birmingham and launched a newspaper in Chattanooga called The Southern Worker, modeled after the Daily Worker. When the arrests happened in March 1931, The Southern Worker was on the ground in Scottsboro—even before major national outlets. “They came to the trials, they interviewed people on the street, and they told the story,” Reidy recalled.

The verdict came on April 9. All nine boys were convicted; eight were sentenced to death. “Later that same day,” Reidy said, “a communique came out of Moscow saying that we need to have mass protests. It was like they were saying, ‘This is the moment. This shows all the flaws in capitalism and democracy.’”

Within weeks, thousands were marching down Lenox Avenue in Harlem. “People were throwing pennies and nickels and dimes out their windows to support the Scottsboro Boys,” Reidy said. By July of that year, an estimated 500,000 people had marched in Germany alone. Every time a new trial or appeal occurred—and there were many—new demonstrations followed. The case became an international rallying cry.

“It was definitely an international event,” Reidy emphasized. “And it stayed in the headlines through the 1930s.”

The Building Itself Holds the Memory

For all its global reach and political resonance, the Scottsboro Boys Museum remains rooted in place—in the walls of a building that tells a story all its own. According to Reidy, physical space isn’t just a backdrop. It’s central to the museum’s spirit and power.

“I think it’s remarkable that we have been blessed with this building,” he told me. “And the story of this building.”

Exterior of the Scottsboro Boys Museum, housed in the historic Joyce Chapel

That story begins with Wiley Whitfield, born into slavery in 1853. His father, a white plantation owner named John Whitfield, was also the master of the household. Wiley’s mother was an enslaved domestic servant, and John’s white wife lived in the same home. After the Civil War ended, John planned to move to Kansas, but Wiley chose to stay. “Apparently, they had a good relationship,” Reidy said, because John left him everything: the land, a grist mill, and a sawmill. “All of a sudden, Wiley… he has all this stuff.”

In 1878, Wiley Whitfield donated the land on which the original Joyce Chapel was built and helped construct it. That first church would burn down in 1903. The one that stands today, the same one housing the museum, was rebuilt in 1904.

To Reidy, that continuity is irreplaceable. “I don’t think you could take this museum, move all these exhibits, and put it in another building—it wouldn’t work,” he said flatly.

The building housing the museum has lived a dozen lives: as a church, a schoolhouse, a gathering space. “It was always like a community building,” Reidy said. In the days when Scottsboro’s Black churches rotated Sunday services, Joyce Chapel was one of the stops. And during World War II, the building served as the town’s Black school throughout the entirety of the war.

That layered spiritual, communal, and educational history adds a moral weight to the museum’s mission. “Our efforts to preserve it are paramount,” Reidy said. “It’s part of who we are.”

The Fight for Pardons: A Dream Realized

If the museum’s creation was a story of memory reclaimed, its advocacy work proved how deeply that memory could matter—not just for visitors, but for the historical record itself.

Scottsboro Boys Museum Executive Director Dr. Thomas Reidy on seeking posthumous pardons for the Scottsboro Nine.

In 2013, after more than 80 years, the state of Alabama officially issued posthumous pardons to the Scottsboro Boys. It was a watershed moment—one born not out of political consensus, but out of persistence. And it wouldn’t have happened without the tenacity of Shelia Washington and the museum she built.

“The process started in mid-2011—for me,” Reidy said. “For Shelia, I think it started years before that. She always wanted to do it.”

Reidy and Washington reached out to the Alabama Board of Pardons and Paroles, a three-person body that makes the ultimate decision. Though the governor’s signature is required, it’s essentially a formality.

After several months, they met with parole board member Thomas Longwood, made their case, and were met with both sympathy and a wall.

“He said, ‘Wonderful, this is a great idea… except that we don’t pardon dead people in Alabama.’”

For Reidy, that felt like the end of the road. “I thought, okay, well, that’s a dead end.” But Shelia had other plans. “By the time we started driving back from Montgomery to Scottsboro, Shelia goes, ‘Well, we gotta start making some calls. We gotta change the law.’”

“She started calling Senator Arthur Orr, Representative John Robinson—she didn’t waste any time.” What followed was nearly two years of grassroots lobbying. They met with legislators, built support, and began laying the groundwork for what would become the Scottsboro Boys Act.

At the same time, Reidy worked to build momentum in public discourse. He contacted a friend at Alabama Heritage, a well-respected magazine with a statewide reach. “I told her, ‘I’ve got to get an article in—this issue coming up.’ These are magazines that want the story six months in advance. This was three weeks. But I explained why it mattered, and she agreed.”

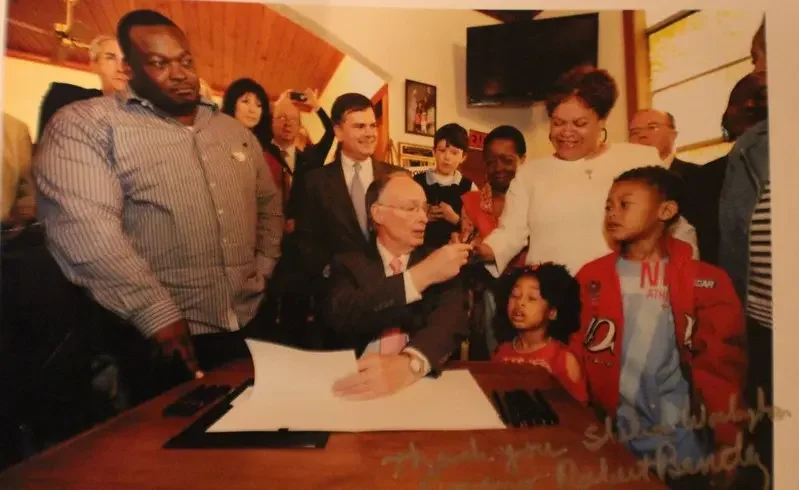

The article was published just in time. “At the end, I said something like, ‘Ultimately, this is in Governor [Robert] Bentley’s hands. Is he going to do the right thing?’” Days later, at a press conference, Governor Bentley referenced the article directly. “He said, ‘I’d love to pardon them—give me something to sign.’”

From there, things accelerated. The Scottsboro Boys Act was drafted and pushed through the Alabama legislature. And on a spring day in May 2013, Governor Bentley came to the museum itself—right into the heart of Joyce Chapel—and signed the bill into law. “He was right here in this museum, right over kind of where we’re sitting right now,” Reidy said.

Alabama Governer Robert Bentley signing the Scottsboro Boys Act into law, 2013

Three months later, the pardons and exonerations were formally issued.

“It was very satisfying,” Reidy reflected. “But again, it wouldn’t have happened without Sheila—not just being fearless, but being relentless. For anyone who runs a nonprofit, to have that kind of guts? That’s something.”

When asked what he remembered about Shelia’s reaction, Reidy recalls an outpouring of emotion. “She cried. She was just so happy… it was a lifelong dream.” At the ceremony in the museum, the house was packed. People sang her praises. They spoke about the significance of the case, the triumph of truth, and the labor of remembrance.

“I think she felt a kind of validation she probably had never felt before,” Reidy said quietly. “It was a real accomplishment.”

And he knew it meant more for her than it could for anyone else. “She had it harder. I don’t live here,” he explained. “Even though I was involved, I didn’t have to live in this community. Shelia bore the brunt of it.”

But on that day, surrounded by celebration and recognition, the burden lifted—if only a little.

“It was such a great experience for us,” Reidy said, his voice softening. “And I’m so happy that she got to experience that.”

Shifting the Narrative: From Resistance to Reconciliation

In the early years of the museum, community reception was mixed—respectful in some corners, resistant in others. But as the years passed, and the museum became not just a place of memory but of presence, people began to see it differently. That evolution didn’t happen overnight.

“We definitely have more advocates here now,” he said. “More allies in the community. And we have people in leadership positions who kind of get what we’re doing and support it.” That shift, he emphasized, has made an enormous difference. “I think it’s improved greatly. I don’t think we’re there yet—we still need to educate people.”

There’s still lingering tension. Some residents continue to wrestle with the museum’s very premise. “‘We don’t want to be known for this,’” Reidy said, echoing a common refrain. “‘So why build a museum just to remind people of something we don’t want to be known for?’”

The response of the museum team is to frame it as an opportunity—not just to confront the past, but to transform the present.

Reidy often invokes Germany’s post-Holocaust public reckoning. “They decided decades ago that rather than not talking about that dark history, they were going to shed a light on it. And in doing so, create newer shared memories and strengthen their community that way.” Scottsboro could do the same, he argued.

Scottsboro Boys Historic Marker at the Jackson County Courthouse

“And we’re beautifying the area,” he added. “These are hallowed grounds… and we want the whole thing to feel as special as it is. It’s beautiful now, but it’s going to be even more beautiful.” That beautification matters. The museum sits on West Willow Street, where disinvestment is visible. A revitalized museum campus contributes not only to cultural preservation but to the literal streetscape.

That kind of impact reaches people who might not have engaged with the museum otherwise.

“There are areas that aren’t necessarily directly related to the Scottsboro story,” Reidy said, “but they get people who maybe were totally against it—or maybe they were 50/50—now reconsidering.”

The museum has embraced creative entry points to meet people where they are. One of the newest projects is a commemorative garden dedicated to Ada Wright, the mother of one of the Scottsboro Boys. “We created a garden committee and thought, okay, let’s invite all the master gardeners in Jackson County,” Reidy explained.

Healing doesn’t always begin with history. Sometimes, it starts in a garden.

The response was heartening. “At our first meeting, like a dozen people showed up—people who had never been to the museum before, who had never found a reason.” And once they were in the door, they wanted context. “For them to understand this garden and how it fits in, they needed to know the Scottsboro story. So now they’re interested. Now they come to our other programs.”

In a town still learning how to hold this history, the museum has become more than a memorial—it’s become a place to enter the conversation. “There are ways to get people involved,” Reidy said. “Meeting them halfway. Holding their hand a little as they walk through the museum the first time.”

One of its most successful initiatives has been a traveling exhibit launched last year. “We went to Huntsville, Birmingham, Montgomery,” Reidy said. “It’s ten banner stands, a couple pieces of art, and we do programs at each venue.”

One of the most significant projects, which consumes most of the museum’s energy and fundraising efforts, is the outdoor space. “That’s our big capital expense,” he said. “We’re working to make it beautiful because these are hallowed grounds. And we want everything around the museum to feel just as sacred.”

For a museum built on grassroots determination, nothing feels quite as meaningful as finally being embraced by the local school system. It took over a decade, but in 2023, something changed.

“Between our opening in 2010 and February of 2023, we had never had a class from Scottsboro visit the museum,” Reidy shared. “It took 12, 13 years. But last year, most of the high school came.”

That shift was hard-won, and it reflects a broader commitment to community collaboration. “We’re going to continue getting the buses here,” he said. “We want to educate students, obviously, but we also want to help teachers.”

And these days, that’s no small thing. “It’s never been more difficult to teach these moments in history,” Reidy said. “Educators come here and say, ‘We don’t know what the rules are anymore.’ But they do know that when they come here, we can talk. And we give them some cover—because if anything is said in this space, they can’t get in trouble for it.”

In that way, the Scottsboro Boys Museum is not just a place of history—it’s a haven. “More than ever,” Reidy said, “museums—especially these smaller grassroots rural community museums—are just so important.”

What Visitors Take With Them

Interior Exhibit, Scottsboro Boys Museum

“The main reaction we hear is, ‘Wow, how come I didn’t know this?’” Reidy said. “How was Adolf Hitler associated with Scottsboro? They start making these connections.” For the vast majority of adult visitors—he estimates upward of 90 percent—that initial surprise is quickly followed by gratitude. “They’re happy to get the information… just shocked they didn’t already have it, especially when they see how important it is to the civil rights movement.”

But for Reidy, some of the most meaningful moments come from less predictable visitors.

“I love when we get a leadership group,” he said, “people who are coming in from different political backgrounds—maybe businesspeople who don’t necessarily walk in already convinced this is important.” These aren’t the like-minded guests who already view racial justice as essential. “If somebody comes in like-minded, I know they’re going to love the museum,” he said. “But if not—I want to hear their feedback.”

And sometimes, that feedback leads to unexpected engagement. “Those people find things in here that they like,” Reidy reflected. “They’re interested in the legal history, how this happened. They can find a way in. And you hope, little by little, that grows into something.”

One moment in particular stuck with him. About a month ago, a visitor followed up with a lengthy email. “He loved everything,” Reidy said. “Said it was great, well presented… all the things you hope to hear.” But then he got to the final panel.

That panel, placed near the exit, poses a mirror of the question visitors are asked upon entry: What would it be like to be a Black teenager in 1931? At the end, it flips the frame: Now imagine what it’s like to be a Black teenager today.

The exhibit includes statistics on mass incarceration, systemic inequality, and references the 2020 protests following the murder of George Floyd. “We show some statistics,” Reidy explained, “and I wrote a line about how the Black Lives Matter movement witnessed millions of people peacefully marching through the streets. It’s a true statement.”

The visitor took issue with that framing. “He said it was incomplete—that we should’ve also talked about all the violence that followed,” Reidy said. “He felt the museum had ‘turned political’ at the end.”

Reidy understood where the discomfort came from. “Maybe he has a point,” he admitted. “It wasn’t intentional, but I could see—if you walked in with the idea that the whole George Floyd thing was about violence—then yes, that line might feel political to you.”

But to others, the line reads as lived truth. “If you marched in those protests, if you were part of that movement, and saw the positivity and the push for real change, then no—it’s not political. It’s reality.”

For Reidy, that tension isn’t a flaw—it’s part of the work. Museums aren’t neutral. They hold up the past, reflect the present, and ask you to sit with both. “We’re not trying to indoctrinate anybody,” he said. “We’re trying to open the door.”

The Unfinished Work of Justice

By its very nature, the Scottsboro case is political. The charges, the all-white juries, the death sentences—all of it unfolded within a system designed to devalue Black lives. And yet, as Reidy discussed, that political reality often gets lost when we talk about the past.

“There’s this challenge people have,” I observed, “of recognizing the intense political nature of Black resistance and pursuit of justice—when it’s in the past. We can respect the ‘60s, but the present? That’s where the line gets drawn.”

When asked how hard it’s been to communicate that through line—the historical connection between Scottsboro and present-day struggles—he said it requires starting even earlier. “You’ve got to talk about the mind of the white jurors,” he explained. “Were they just dumb? Uneducated? Couldn’t they see what was before their very eyes?”

Interior Exhibit, Scottsboro Boys Museum

Understanding that foundation—the eugenics, the pseudoscience, the deeply embedded ideology—is crucial. Otherwise, as Reidy put it, “You’re becoming bigoted in your own way. Because what you’re saying is: the reason they decided Haywood Patterson was guilty is because they were stupid.”

But it’s not that simple. “We need to get into their minds more. Understand the fear. The group mentality. There was real violence at the time. A juror who didn’t vote to convict was putting his life in danger—his family’s life in danger.”

They weren’t just voting; they were conforming. “There was a mindset that they needed to convict to protect white society,” Reidy said. “And they were afraid not to go along.”

That kind of pressure, that kind of fear-driven complicity, still echoes. Whether it’s in classrooms where students are afraid to speak about race, or in institutions that punish people for trying, Reidy sees the connection. “If we’re going to talk about resistance today, we have to talk about how white supremacy works—not just as hate, but as structure, as fear, as silence.”

With all the weight this story carries—systemic racism, global solidarity, grassroots courage—what does the Scottsboro case still have to teach us about resistance, dignity, and the unfinished work of justice?

“I think the last thing is the most important—that justice is unfinished.”

People often wonder if a case like this could still occur today. Most say no. But then someone always reminds us: it does. “We still find instances of injustice every day,” Reidy said. “And the case teaches us that when there’s a cause that is righteous… when something involves gross unfairness, people from such diverse cultures and backgrounds can come together.”

It’s a documented truth. “We had Latvians—Latvians who had never been to the United States—protesting to free the Scottsboro Boys,” Reidy said. “It shows there’s this community of conscience out there. And I think that still exists. I know it still exists.”

That’s what the museum is trying to activate—not just memory, but conscience.

“When people leave the museum, we hope they understand the story better,” he said. “But I also hope they have a little bit of a sense of outrage. Not that they’re going to go do something criminal—but that they do something.”

“It’s the ones who do nothing that are the biggest threat,” Reidy said, reflecting on Martin Luther King Jr.’s quote: “He who passively accepts evil is as much involved in it as he who helps to perpetrate it. He who accepts evil without protesting against it is really cooperating with it.” He added, “So that’s what I hope people do when they leave this museum.”

Not just remember—but act.

Follow and Support the Scottsboro Boys Museum

Instagram: @thescottsboroboysmuseum

Facebook: facebook.com/sbmuseum

YouTube: youtube.com/@TheScottsboroBoysMuseum

Website: thescottsboroboysmuseum.com